Jay A Gertzman, author of Beyond Twisted Sorrow: The Promise of Country Noir, explores some of the archetypes in literature that have helped shape the growing rural noir subgenre…

If you care for Westerns, you have read about Shane, the lone rider whose gun frees a homesteading community from a cattle baron, and then rides off, although injured, leaving the boy who tells his tale to wonder at Shane’s need for lone wilderness. And you also probably know about Jill in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. Her family was murdered so that a railroad CEO could make a fortune by reaching the Pacific. She had the guts and brains to organise settlers to build a beautiful town, flourishing under law and order. She would eventually provide citizens with financial (railroad) and cultural (opera house) advantages.

Shane and Jill are two icons of the Western hero(ine). John Caweli nails it: the former must have the “life of the wilderness, and the other gives all for advance of civilisation.”

Choosing wilderness

John Williams’ Butcher’s Crossing describes an 1870s buffalo hunt during which two mountain men and Will Andrews, a novice from Harvard, must endure near death from hunger, thirst, stampede, uncharted wilderness, a diet of raw buffalo liver and rot-gut coffee, and a snow-bound winter in a makeshift dugout. After returning to the Crossing, the former novice sets out alone, not knowing where he is going, but addicted to the danger, beauty, and vastness of the Rockies. Will had “sloughed off his old skin.” The phrase is DH Lawrence’s, describing a radically American aspiration.

Letting nature teach survival

In Chris Offutt’s The Leaving One, a story in his Kentucky Straight (1992), Vaughn Boatwright, on the edge of manhood, finds in the brush a man in ancient buckskin, festooned in twigs and leaves. It’s his grandfather Lige, exiled from the family for disrespecting a clergyman. He sustained himself by living in the woods, letting nature show him how to survive. Lige takes Vaughn deep into the wild for a mysterious walk, teaching Vaughn how to let animals and trees show him how to stay alive.

Eventually, Lige lies down. While Vaughn searches in vain for a heartbeat, the imprint of his body becomes outlined on his grandfather’s. An old buck stands on one side. Cries of bear, bearcat and hawk make it seem “all the hills were rushing to the oaks.” Vaughn had forgotten the way back, but an uncanny force “moved to his back and stopped.” He recognized it and proceeded unafraid down the hill and through the woods, beloved of the wilderness with which his grandfather has merged himself.

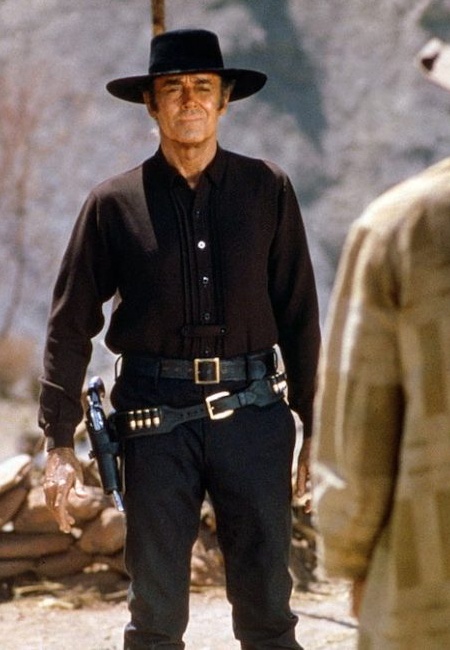

A shootist

In Beyond Twisted Sorrow: The Future of Rural Noir, I focus on an old west gunman who outpaces even Bill Hickok in quick draw accuracy. He is John Bernard Books, hero of Glendon Swarthout’s 1975 Spur Award novel The Shootist. Books, afraid of nothing, scourge of hypocrisy, fighter against illness and pain, and impassive killer (as many as 30; five on his last day), personifies “bone lonesomeness.” He hates cities and is only in El Paso to find relief from a terminal illness. Like other Western heroes who must experience the chaotic mystery of the nature of which we are all a part, Books went solo, talking to God as a rival whom he dares to kill him. That is hubris, the ultimate wild freedom. Swarthout contrasts it to the mundane endeavours of El Paso’s solid citizens: a “sinner confess” minister, a former lover (who wants him to sign a contract for a ghost-written tell-all), a photographer and a pulp writer both smelling a profit, and a publicity-avid undertaker: all small, money-mad nonentities.

And the reverse of the medal is there also. When he is waylaid by an old, desperate thief at gunpoint, Books shoots him and offers him only an easy death with a shot in the robber’s head. Books chooses the day he will die, in a gunfight against a half dozen of the city’s worst and most oppressive gangsters. He kills them all, and only then succumbs.

Other chronic confronters of wilderness include AB Guthrie’s Boone Caudill (in The Big Sky), a misanthrope who kills an Indian for his horse, picks fights to relieve people of prized possessions, rapes a schoolmate, and shoots his best friend on the false supposition that he bedded Caudill’s wife. Then he abandons the woman, and his own son. A man of enormous physical strength, he escapes an Indian massacre by swimming for hours with only his nose above water. He is about to strangle his mentor when the latter’s partner kills Caudill, so that his victim, a man of moral probity, can continue to live.

John Grady Cole, horse whisperer

Cormac McCarthy presents, in Cities of the Plain (the third novel in his Border Trilogy), the concluding adventure of John Grady Cole. He seeks, in sinister, exotic Mexican highlands, a female of otherworldly innocence. It is an exemplary gothic tale, one that displays a biblical universality. The bible itself has both noir and gothic passages, and at this stage of his career, McCarthy might be deemed a religious as well as crime writer. He describes the merging of human with nature’s actions and reactions, and stresses the sense of loss in the characters with the passing of years. Part of that is implied in the setting, near the nuclear testing facility of Alamogordo, New Mexico. But the mysterious Mexican borderlands are where the most gothic events transpire.

Cole is an exemplary cowboy; still in his late teens, he is the best horse trainer in the West. He is also an uncanny healer, and protector, of wildlife. He is in love with the innocent Magdalena (“she does not belong among us”), trapped in a Sodom, an expensive whorehouse run by Edwardo, a sinister example of capitalist wealth and power, who paradoxically also loves Magdalena. In a nightmarish knife fight in which Grady and Eduardo show instinctive and calculating skill, Eduardo slashes his initials in Grady’s thigh but Grady delivers a killing blow to Eduardo’s jaw. Meanwhile, however, Magdalena has had her throat horribly slashed open. Grady dies from loss of blood. In an Epilogue, many years later, Grady’s best friend Billy, after conversation with the Devil, finds a caring couple to take him in.

Western city builders

There is an equal variety of Western heroes who are champions of law and order, and the founding of beautiful towns. None are in the trap that the sheriff in McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men faces. He is up against a new kind of human dominator for whom others are mere sugar for ants. Some successful authority figures are frontier marshals, such as Bat Masterson, Bill Hickok and Wyatt Earp. They sometimes persuaded dangerous men to leave town instead of standing trial. It might not have served the ideal of justice, but it prevented a lot of bloodshed, which would have made it hard for a camp to gain the status, and the variety of citizens with administrative and technological skills, that a growing and prosperous town would need. Wyatt Earp often made deals and shared information with rustler Ike Clanton, later an opponent at the OK Corral shootout.

The day Bill Hickok was shot, in Deadwood, where he held no office, there were rumours that he was to be appointed marshal, in order to stop the dance hall racketeering, including pimping, extortionate loans, rustling of horses and cattle, the wild shoot-ups and shoot-outs by drunken cowboys, the thievery and intimidation of prospectors, and the defiant carrying of firearms in the streets and eating places. Hickok had to go.

Beyond Twisted Sorrow gives a lot of space to Tom Franklin’s Poachers. In it, a vengeful game warden has avenged the killing of a colleague by killing two, and blinding the third, of the killers. He allows the deaths to be attributed to mere chance. The sheriff may be making it easy on himself by not pursuing justice, but he also has his head screwed on right. He has a perseverant human-sized response to the inevitable. The townspeople in the remote Lower Peach Tree respond to a spring flood by bailing out and carrying on. That is what the sheriff is doing, ignoring the moral and social confusion of a trial in which the game warden would be exonerated and thus allowing the community to go on with their necessary workaday tasks in relative peace.

A prescription pain capital

Similarly, the sheriff in Sheldon Compton’s Brown Bottle must deal with a similar evil: a struggle for control of the drug-dealing market in eastern Kentucky’s “prescription pain capital.” As Sheriff Bell sees it, both users and peddlers living in symbiotic cooperation with the police is in their own and their families’ best interests. It is good for business. Because of the many court cases to be adjudicated, lawyers and bail bondsmen move into town, buying or renting houses, purchasing high-end home appliances and paying taxes. A multifaceted collaboration between newcomers and natives on the one hand, and underworld and elected officials on the other, has evolved. It makes for economic stability.

The most admirable, but also quixotic, proponent for community is the self-appointed mayor of Hard Times, in EL Doctorow’s eponymous novel. Having travelled widely throughout the frontier West, he realises that a community flourishes due to its people’s ability to feel a need for not just business like tolerance but kindness for each other. He must prepare his townspeople for a second coming of a devil, a bad man from Bodie.

For more investigation of rural noir and its roots, Beyond Twisted Sorrow: The Promise of Country Noir by Jay A Gertzman is available now.