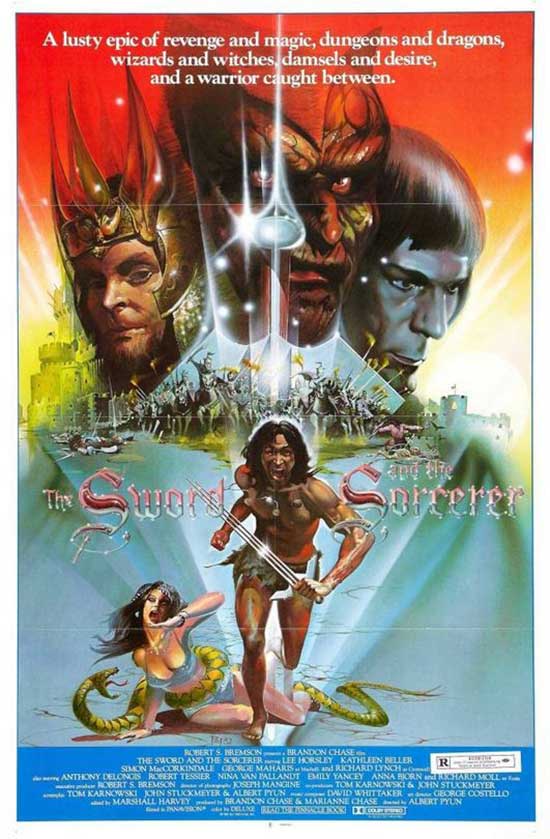

The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982) sometimes appears in horror movie resource books, despite being a “fantasy” film. Maybe including the film is appropriate. Fantasy often serves a mix-and-match genre, with horror creatures finding their way into a sword-and-magic tale. The marketing and distribution team that cut the epic theatrical and TV trailers stressed frightening horror elements – witches, deformed sorcerers, shadowy tombs, gratuitous violence – targeted terror film fans, along with those who enjoy high adventure.

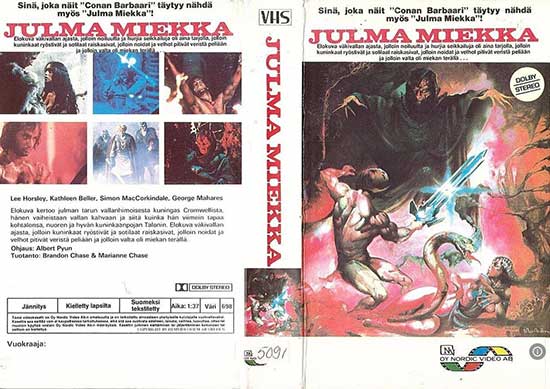

The mix-and-match worked. The Sword and the Sorcerer’s creative talent, director/writer Albert Pyun and co-writers Pyun and Tom Karnowski and John V. Stuckmeyer, and producers Branden and Marianne Chase understood that putting garish horror elements and exploitative adult content would guarantee an R-Rating and stir up interest on the drive-in and dive theater circuit. They succeeded far beyond expectations, as the film earned nearly $40 million at the 1982 box office and furthered its cult following in 1983 and 1984 with prominent cable television airings and VHS distribution.

Looking back, a path to the film’s success already existed. Horror films generally did well at the box office, and audiences tired of the slasher cycle looked for something new. Sword-and-sorcery showed box office potential, and action/adventure features were on the march to 1980s greatness. The Sword and the Sorcerer pushed fantasy’s genre-blending elements to captivate audiences looking for dark heroic escapism. Helping things was the promotional push for a certain upcoming Arnold Schwarzenegger film.

The Sword and the Sorcerer had an outstanding promotional campaign, too. The incredible television spots featuring Lee Horsley’s character, Talon, shattering four bad guys’ swords with his iconic three-bladed weapon grabbed attention. You had to see this offbeat, unpretentious fantasy film that presented high adventure, traditional heroes and villains, a simple plot, lots of fighting, and, yes, horror. What kind of horror did the film display? Just as fantasy mixes clearly defined aspects and tropes from other genres, the umbrella category also borrows subtexts from those genres.

Subtext is often psychological. Fear remains an essential component of a horror film, and all three main characters, Talon, Cromwell, and Xusia, display different levels of internal fear.

Of course, there is much outright horror to fear, too.

The Horror of It All

Horror creatures such as the undead sorcerer reflect an overt nod to the horror genre. However, horror remains mostly subdued in The Sword and the Sorcerer’s narrative, as action and swordplay carry the day. At times, horror takes a more prominent role, either through human monsters such as Robert Tessier’s Verdugo the Torturer or the supernatural Xusia.

Through these characters, the film notches the violence up further than what audiences would see in even fellow R-rated fantasy fare like Excalibur (1980) and Conan the Barbarian (1982), and far, far more than PG features such as Dragonslayer (1981). The Sword and the Sorcerer shifts to horror film-level violence at specific story points, delivering shock value before stepping back to allow whimsical high adventure and fight scenes to pick up the pace.

Supernatural horror elements bookend the film, which begins with Xusia’s awakening and concludes with Xusia’s attempt at vengeance. The final battle of good vs. evil and more evil pits Talon and his majestic sword against the evil King Cromwell and the enraged Xusia. The sorcerer adds horror to the mix by ripping apart his flesh-covered disguise, appearing covered in gore and looking like a more menacing dead ringer of the decayed conquistador from Lucio Fulci’s Zombie (1980).

Between the outright horrors of the opening and closing, psychological horrors linger.

Fans may debate the “true” meaning of horror, but Merriam-Webster offers a straightforward definition:

Horror: painful and intense fear, dread, or dismay.

There’s nothing supernatural found in those words. When Talon faces one stairwell full of sword-wielding soldiers to his left and even more sword-wielding villains to his right, the hero certainly experiences dread and dismay. Likely terrified inside at impending doom, Talon never shows fear, responding with cocky confidence, “Who dies first?”

The subtext of psychological horror, while not as apparent, lurks beneath the surface and inside the lead hero throughout. The same may be true of the antagonist.

Death by several dozen butchering palace guards reflects a horrifying end, but not an unrealistic horror. However, iconic screen villain and horror icon Richard Lynch’s Cromwell finds himself in a truly horrifying and otherwordly initial meeting with a grotesque sorcerer Xusia.

In an extended prologue set eight years earlier, Cromwell relies on a servant witch to bring Richard Moll’s aged sorcerer back from the dead. Xusia rises from his slumber in the “Crypt of Souls,” where stone-carved faces come to life, screaming. The sorcerer rises from a vat of blood, covered in crimson, and rips a servant’s heart from her chest to prove his might.

Cromwell, like Talon, shows no outward fear. He points his sword in Xusia’s direction, a perilous move. Cromwell wants Xusia’s power to take young Talon’s father’s kingdom away, but please do not think he’ll yield to the sorcerer. Cromwell’s bravado comes with no bluffs.

Fear, dread, and dismay never once enter Cromwell’s mind. Horror characters rarely strike fear into fellow villains. Truthfully, as evil as the immortal sorcerer Xusia is, the all-too-human Cromwell is worse.

Talon and Crowwell Face Horrors

Merriam-Webster delineates the distinction between horror and horrors:

Horrors: plural: a state of extreme depression or apprehension.

The definition fits Talon’s mental state perfectly. The hero might not behave that way, as he carries himself as a comedic version of the classic pulp character. Talon’s a carry-over from the light-hearted late 1970s pop culture mixed with the slowly developing action hero of the 1980s forges a 1930s sword-wielding adventurer’s cynicism with Rodger Moore’s James Bond’s attitude towards life. Like Moore’s Bond, the comedic approach Talon takes could serve as a way to cover up the pain associated with the violent life – past and present – he lives.

The young Talon, seen at the film’s outset, finds himself in extreme depression when he watches Cromwell slaughter his father, mother, and siblings. During the lost eight years where Talon grew into young adulthood, he became a skilled fighter, respected mercenary leader, unabashed carouser, and master of light comedy. The character never loses a drive for revenge, and simmering anger remains beneath the surface, anger focused on revenge against Cromwell.

Indeed, that internalized and externalized anger connects with the wayward hero’s depression over his family’s death and the life that “could have been.” Prince Talon, of course, is the rightful heir to the throne Cromwell stole, a throne Talon shall never occupy.

Talon’s nemesis Cromwell might not appear depressed, but the tyrant has his apprehensions.

If someone’s immediate response to watching an undead sorcerer telekinetically pull out a woman’s heart involves pointing a sword at the macabre mage and threatening him, “apprehensive” doesn’t seem like an apt description.

Cromwell backs up his bullying bravado. He displays prowess when threatening Xusia and, years later, challenging Talon to a one-on-one sword duel, refusing any help from his soldiers. Cromwell maintains confidence in his fighting abilities, hardly showing any apprehensions.

However, fear may still drive Cromwell’s lust for power. Tyrants who use force to steal thrones typically fear someone else will plot the same. Mad kings make scores of enemies, powerful ones. They rely on immoral officers and foot soldiers, characters whose loyalties might shift without warning upon receiving a better offer.

Fear takes different forms — Cromwell’s internal dread circles the horrors of losing the throne. Feelings of inadequacy drive him to conquer more kingdoms and consolidate more power. That makes him a dangerous tyrant.

Talon and Cromwell’s Anxious Terrors

Heroes and villains have quests and goals. The villainous Cromwell wishes to conquer more kingdoms so “one man will control the entire civilized world,” while Talon seeks vengeance for his family’s demise. Both hero and villain connect their identities to achieving these ends, and failure comes with the consequence of personal failure. Expect an anxious nervousness lying hidden in both characters’ psyches.

Cromwell derives his self-worth from his kingdom. Desires to expand the kingdom underly internal insecurities. Although Cromwell may well be a field commander and skilled fighter, such things do not necessarily reveal or require self-confidence. Sometimes, these behaviors exist to mask low self-esteem.

Cromwell’s decision to seek aid from Xusia shows the brutal monarch knows he lacks the necessary abilities to defeat King Richard. Bold bravado in the face of the newly-revived sorcerer does not hide the reasons why Cromwell asks for aid, so he doesn’t ask. He half asks and half threatens. Later, betraying and attempting to kill Xusia may have nothing to do with exiting a partnership as much as ridding oneself of the living reminder of not cutting it.

Talon may suffer from similar deep-rooted problems.

The kingdom rightfully belongs to Talon, but he knows the path he traveled in life makes assuming the throne impossible. He’s a wanderer and an adventurer. Redemption for him involves slaying Cromwell and putting an honorable person on the throne. Before and after The Sword and the Sorcerer, Talon’s off-screen adventures may or may not give his wayward life meaning. As a mercenary, he’ll receive payment. Perhaps some adventurers would serve a greater good. The battle against Cromwell would be his most important one, and Talon’s humorous musing may try to hide his worries about possible failure. After all, the odds of overthrowing a kingdom seem low.

Fear of failure haunts both Cromwell and Talon. More troubling, the specter of a vengeful Xusia lurks. And the sorcerer has his own problems.

Xusia’s Accidental Horrors

Although referenced in the film’s title, the sorcerer Xusia receives little more than a cameo role. Don’t assume he’s merely a foil unessential to the story. The character adds a vital fantasy-horror element, leaving audiences with an “anything may happen” attitude as they watch the proceedings unfold. Xusia’s horror character does more than inspire fear. He suffers from it.

Ultimately, Xusia fears his impotence.

When Cromwell threatened Xusia during their first meeting, the would-be tyrant did so after his bodyguard outright insulted the sorcerer, calling him a toad. Xusia responded by tearing the heart out of an innocent witch, the one who brought him back to life. Why didn’t Xusia kill the bodyguard and, for that matter, Cromwell? All-powerful sorcerers don’t typically take kindly to impudence.

The reason is that Xusia had something to prove.

Few would dismiss his power since Xusia’s conjuring gave Cromwell’s army the ability to best King Richard’s. Cromwell knows extensive conjuring leaves Xusia weakened, and Xusia let his guard down. Perhaps the weakened state dulled his senses and judgment. Regardless of the reason, Xusia nearly meets his demise in a double-cross. Unless the sorcerer finds a way to gain revenge against Cromwell, he must settle for an embarrassing legacy: the great sorcerer who let himself become one-upped.

Unless Xusia takes Cromwell’s throne, bride, and life, the sorcerer remains the fool, and that’s a horror beyond the warlock’s imagination.

Riding Away from the Horrors

Adventures come to an end, and The Sword and the Socercer concludes expectedly. As the song goes, Cromwel is gone. Xusia is gone. And Talon is gone. Talon doesn’t meet his demise but he knows this is no place for a hero like he is. Along with his mercenaries, Talon heads off a new adventure and a chance to tell the tale of saving an ancient empire.

Talon rides off with a smile on his face, suggesting he put to rest the demons from his childhood. Of course, no one could every put their family’s murder out of their mind. Likely, Talon will continue to use humor and escapist adventures to hide trauma. That’s no fantasy. It’s an unfortunate true-life horror.