The Lincoln Memorial is iconic in the history of the Civil Rights movement. It was on the steps of the memorial to the President who signed the emancipation proclamation that Martin Luther King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech (which this country continues to view through a sanitized lens) during the March on Washington in 1963. And just 24 years prior, the Memorial was the sight of another watershed moment for civil rights and the fight against racial prejudice and segregation that is often forgotten: the groundbreaking concert from singer Marian Anderson on April 9, 1939.

In 1939, Marian Anderson was at the height of her operatic career. The contralto had sung on stages across Europe to immense acclaim and “Marian fever” from fans, finding greater success there than she had in American due to racism, but her star was now rising in the US as well. Since 1935, Anderson had given an annual concert at historically Black Howard University in Washington DC, and become a favorite of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Her concerts had become more and more popular. Howard could not accommodate the audience in 1939, and requested to hold the concert at Constitution Hall, the largest venue in DC at the time.

There was only one problem. Constitution Hall was owned and run by the Daughters of the American Revolution and the DAR had a policy that barred the use of the hall by Black performers. They denied Anderson permission to use the venue for her concert. Charles Edward Russell, a co-founder of the NAACP, organized groups including the National Negro Congress, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the American Federation of Labor, the Washington Industrial Council-CIO, and many other activists and church groups into the “Marian Anderson Citizens Committee (MACC)” to protest the decision and plan mass action.

Because of the attention brought to the matter and the actions taken to organize for Anderson, thousands of DAR members would resign, including Eleanor Roosevelt. Roosevelt publically chastised the DAR for the decision and resigned from the group, increasing the media furor. “You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way,” Roosevelt wrote in her “My Day” column, which was syndicated nationally, “and it seems to me that your organization has failed.”

The outcry was vocal, with artists and organizers calling for Anderson to be given a different venue in the Capitol. Lulu V. Childers, one of the organizers with Howard, promised: “She’ll sing here, even if we have to build a tent for her.” Roosevelt, working with Walter White, then executive secretary of the NAACP, came up with an idea and pulled in Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, to invite Anderson to sing in front of the Lincoln memorial. No one could deny the Secretary (and the First Lady by association).

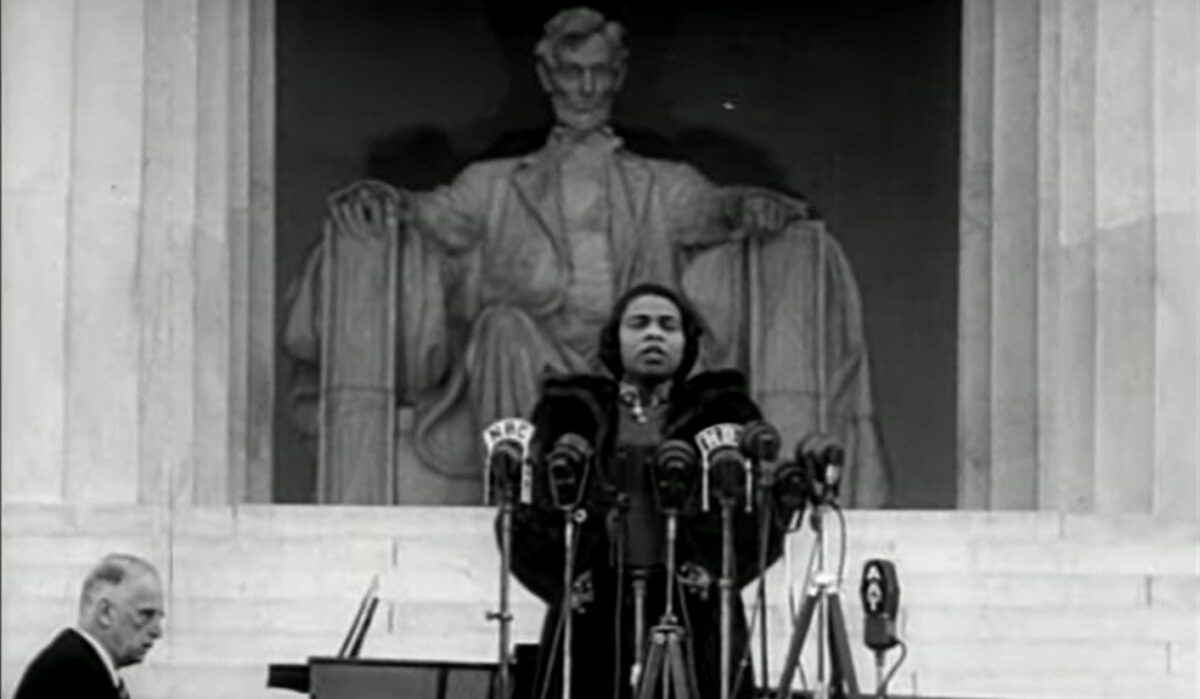

On Easter Sunday, April 9, 1939, Ickes introduced Anderson with the words: “In this great auditorium under the sky, all of us are free. Genius, like justice, is blind. Genius draws no color lines.” Anderson took the stage before an integrated crowd of over 75,000 people and a radio audience of many millions and raised her glorious voice. Her first selection was “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” And she changed the words “of thee I sing,” to “of thee we sing.”

It is so clear watching this and other footage how deeply Anderson felt the weight of this moment. She kept her eyes closed for much of the concert, as the statue of Lincoln looked on behind her and she made history. As this newsreel notes, everyone has gathered to hear the voice acclaimed as “the finest in a century,” and as you listen to her, you understand why. After “My Country Tis of Thee” she sang “Ave Marie” and an aria from La Favorita, then for the second half, turn to gospel and Black spirituals, singing “Gospel Train,” “Trampin’” and “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord.” Her encore was: “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.”

The legacy of Marian Anderson lives on in what she did in that moment and the grace and dignity with which she stepped into the international spotlight. Decades before Martin Luther King Jr. would lead the March on Washington and speak from that same spot, she stood up with the whole world watching and made history with her stunning voice. She took a bounding leap on a long road that we are still following, and it is one that should never be forgotten.

(Image: UCLA/Screenshot)

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Have a tip we should know? tips@themarysue.com