I knew there was something different about my voice on public radio when I saw a comment on social media that said that I sounded like “a rapper.”

Now, I’ve been known to drop a few hot bars in my life, but I don’t think that my reporting on the Trump White House at the time contained much intricate word play or any incredible flow. It was clear that the person who tweeted was responding to hearing a distinctly Black southern female voice on NPR. And they weren’t saying it as a compliment.

While I’ve received a lot of positive responses to the way I sound on the radio since I started at NPR in 2018, I’ve also heard a number of complaints along the lines of the “rapper” tweet. The way I speak on air has been called unprofessional, loud, obnoxious, lazy. My intelligence, age, and training have been questioned. It’s been the subject of a whole podcast episode by New York Times columnist John McWhorter! Even with the compliments—which I really do appreciate—there’s an acknowledgment that my dialect stands out.

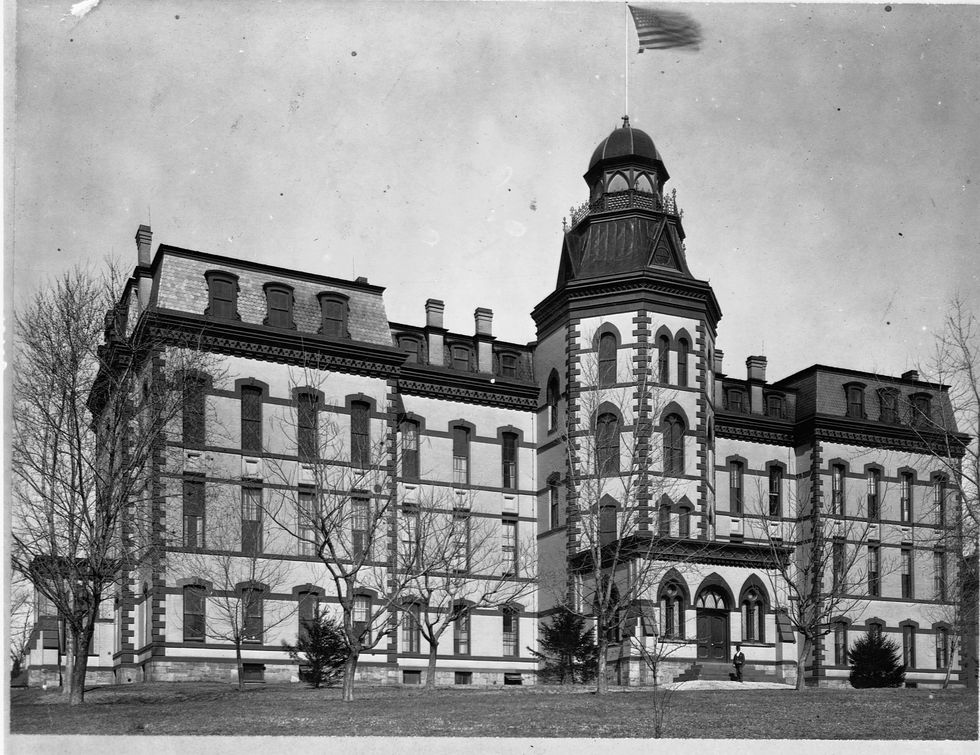

The voice causing all this conversation comes from spending my formative years around Black people in Durham, North Carolina. The confidence to present myself as I am was shaped and molded at Howard University, a historically Black college.

It was there that I saw Black people doing everything: leading, serving, teaching, growing, failing, fighting, persevering, rising. Standing on the shoulders of giants who attended my alma mater like Thurgood Marshall, Zora Neale Hurston, and Isabel Wilkerson, I learned that I should always come correct and give the best of myself, not because white people are watching, but because the world will be better for it.

Much of my time at Howard was defined by my work for the student newspaper, The Hilltop. I remember so many pep talks from Professor Yanick Rice Lamb, the faculty advisor for the paper at the time, who encouraged me to keep going when university administrators bristled at coverage they felt put the school in a bad light. Professor Lamb always made sure that I knew that it was important that we push for the truth even if it ruffled feathers. It cemented the idea in me that to love something is to hold it accountable.

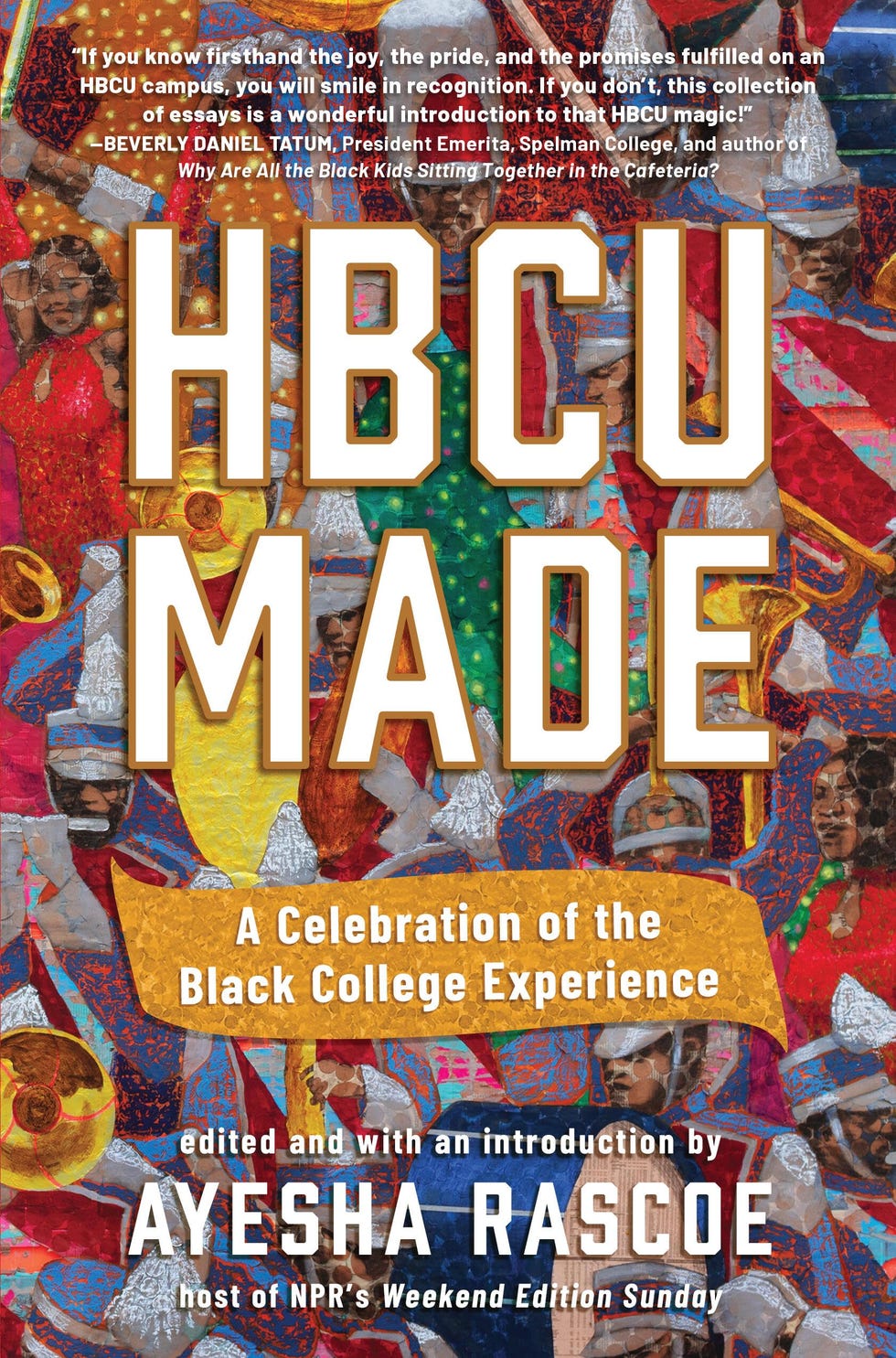

I’m not alone in having experiences like these. As I put together a collection of essays from HBCU graduates from all sorts of backgrounds, titled HBCU Made, I saw stories over and over of these historic institutions allowing people to embrace their identity in a world where being Black is viewed as being the “other,” remarkable and yet still somehow less than.

HBCUs expand the perception of what authority looks like by training leaders from the broad range of the Black experience about what it means to stand in their authentic power. These institutions offer a safe haven for Black students to develop a sense of self—a voice—outside of the harsh gaze of white racism.

“A dear friend once described her tenure at Spelman as a respite from a world that could never truly see her,” writes former two-time Georgia gubernatorial candidate, Stacey Abrams, a Spelman alum, in HBCU Made. “I would add that it was the place where I had the ability to see more of myself.”

The drive and activism that would eventually shake up the political landscape of Georgia was nurtured and guided at Spelman, where listening to Black women is not just an empty mantra. It was on that campus where Abrams ran for her first political office, freshman class secretary. She also began attending city council meetings at the advice of her political science professor.

In classroom debates, “I did not argue from the ‘Black’ perspective or the ‘woman’s’ perspective but as an individual able to think beyond the thoughts taught by people too willing to share their own ideas at the exclusion of mine,” Abrams says.

The late Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison (a Howard University alum), said that “the function of racism … is distraction.” Being in spaces where you constantly have to justify your worth exacts an unspeakable toll. There are very public campaigns that attempt to discredit and degrade Black leaders, like the Pulitzer Prize-winning creator of the 1619 Project, Nikole Hannah-Jones, and the scholar Claudine Gay, who was ousted as Harvard’s president.

Then there are the much more private incidents that seek to diminish us. In her essay for HBCU Made, poet and writer Nichole Perkins talks about a demoralizing instance in graduate school at Ohio State, where she was singled out in class and questioned about how she was able to arrive at a correct answer, as if the knowledge should’ve been beyond her comprehension.

Her undergraduate years at the HBCU Dillard University in New Orleans were very different.

“At Dillard, I didn’t have anyone questioning my intelligence or talent. If someone asked me to prove a claim, it was either to shore up my argument or expose the cracks in it, not to prove I was capable of thought,” Perkins says.

Still, HBCUs are not infallible and have been fertile ground for a certain kind of respectability politics that argued Black people have to look and sound a certain way in order to succeed in a world dominated by white people. During my time in college in the early 2000s, it was not unusual to be warned against wearing braids or other natural hairstyles to job interviews. Thankfully, those mores are falling away with the embrace of the CROWN Act around the country.

And HBCUs certainly do not always offer protection from tragedy, as we saw in the recent heartbreaking suicide of former Lincoln University administrator Antoinette Candia-Bailey.

But when you equip students with the tools to examine the world around them and cultivate a conviction that their experiences matter, it’s not surprising when they feel emboldened to push for their beloved universities to live up to the promise of their founding: to educate free Black people. There is a rich history of student protests at HBCUs. Howard, in particular, had a takeover of the school’s administration building in 1968 that resulted in the creation of African-American history courses. Much more recently, sit-ins at the university over campus living conditions have gained national attention.

I wish I could say that I entered Howard in the fall of 2003 with that level of audacity. I was timid and shy, but determined to make it as a journalist. When I was eventually chosen to be editor-in-chief of The Hilltop I remember that one of the departing seniors, Shani Hilton (who is a very successful journalist now) told me to put a little more bass in my voice. What she meant was that I should lean into my power. She was right. It didn’t happen instantaneously, but over time the seeds that were planted at Howard took root.

So, years later as a correspondent and now a host at NPR, when people dissect my language and my sound, I can reach back to my education and understand that it’s really not about me. That’s not to say that it’s not infuriating and at times hurtful to feel like my intellect and work ethic are up for debate. But, I understand that people are reacting to hearing a voice that they don’t associate with authority delivering them the news. When they hear me, I hope they hear my southern, Pentecostal church upbringing. I hope they hear my mother, my father, my grandparents, my family. And I hope they hear the Howard in me, even if they call it rapping.

Ayesha Rascoe is the host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday and the weekend episodes of Up First. Prior to her role as host, Rascoe was a White House Correspondent. She covered three presidential administrations. As a part of the White House team, she was also a regular on the NPR Politics Podcast. Before joining NPR, Rascoe spent the first decade of her career at Reuters, rising from a news assistant to an energy reporter to eventually covering the White House. While at Reuters, Rascoe covered some of the biggest energy and environmental stories of the past decade, including the 2010 BP oil spill. She’s a proud graduate of Howard University.