Leanne Pero, the 34-year-old South Londoner, community dance advocate and founder of BAME cancer support group, Black Women Rising, speaks to GLAMOUR’s Elle Turner about the reality of being a woman of colour with a cancer diagnosis.

“Before I set up Black Women Rising, I was told not to make it about black people in case I was trolled,” cancer campaigner and breast cancer survivor, Leanne Pero, tells me over the phone. “Which is exactly what happened.” After the BBC ran a small piece about the group, Leanne had white women message her on Instagram. “They’d say stuff like, ‘why are you making it about black and white?’ Or, ‘What, so white women with breast cancer don’t need support too?’ I had to turn the comments off,” she says.

It’s an uncomfortable truth to swallow, but the reality for many black women is that their experience of cancer – from the support they receive at home, to the way they’re treated in hospital – is entirely different to the experience of white women. This is fact. A study from 2016 (note there’s not been one since as statistics around black medical care is scarce, to say the least), found that many medical students were approaching their patients with an underlying and unconscious bias that influenced how they measured and distributed pain relief. “Racial bias has perpetuated false beliefs such as that ‘black people’s skin is thicker than white people’s skin’” the study discovered. It found many believed that black people’s nerve endings are less sensitive than white people and that black people’s blood coagulates more quickly.

Sinister and deep-rooted notions carried over from the past continue to manifest today in unconscious and un-founded assumptions about the physiological make up of black bodies. The study found that, white medical students who held inherited and ingrained beliefs that black people can tolerate extreme heat more than white people, “were more likely to think that black people feel less pain than white people.” These latent and systemic biases result in research that suggests “if the patient is black, then their pain will likely be underestimated and undertreated compared with if the patient is white.”

But the lack of understanding and care for black patients is perpetuated on both sides. “Cancer is stigmatised in the black community,” says Leanne. “There’s a lot of shame. You keep it within your family, you don’t talk about it,” she says. “Black women have been told cancer ‘isn’t a black disease’ or that it’s karma or a curse for something we’ve done in the past. The worst thing is lots of women have been told not to get chemotherapy or life saving drugs, because it’s ungodly.”

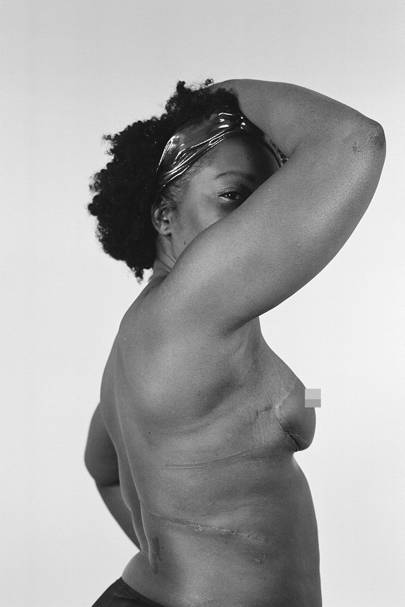

Leanne’s picture taken for the Black Women Rising Exhibition showing in 2021

Naom Friedman

“Women are expected to get on with their cancer treatment quietly, pick the kids up from school, come home and cook the dinner for the family,” she says. “I’ve been presented with stories from women who had been banished from family events so as not to upset others. People worried about catching it from them.” One of the women was even told “don’t worry, I won’t tell anyone,” when she told her family about her diagnosis. It’s seen as something embarrassing and shameful. It’s a topic Leanne’s discussed openly on her Black Women Rising Podcast (another resource for BAME women looking for a support network). One recent guest speaker, Della, confided, “I was told, ‘you eat white people food and you live in a white people area and that’s why you’ve got it.”

“The myths that are plaguing our communities are ultimately stopping our people from getting checked if they feel something is not right, it’s stopping women of colour from accepting vital life-saving treatment once diagnosed and it means many are not reaching out when they suffer with severe mental health after cancer,” says Leanne.

The shame and denial has led to a lack of education among some in the black community when it comes to cancer and plays directly into how their care is managed, whether they’ve done the research or not. “We’re often told by professionals; ‘This is what’s going to happen to you,’ no discussion. Minority women are often ignored and feel like they have no say in their own treatment,” explains Leanne.

The experience on the actual ward can be upsetting, also. “I saw it firsthand, when I went to visit a couple of the women from our support group while they were having treatment. I remember with one of the ladies, the alarm on her equipment was going off so she rang the bell for help. She had to raise her hand several times and when the nurse came over, she just rolled her eyes and turned it off,” Leanne tells me. “I’m not saying that’s because she’s black, necessarily, but I’m saying that there needs to be more education for medics around the background of the women in their care. If only they knew what they’d been through and how much it took for these women to be in those chairs.”

From the Black Women Rising Exhibition showing in 2021

Naom Friedman

The advice around checking symptoms also isn’t reaching black communities who have been excluded from the conversation for so long. “When I was diagnosed, I was shocked,” Della admits. “I didn’t know anyone else who had it. But all the leaflets I could find were of white people, which is why I became so vocal. I’m like look, help us to help ourselves. I spoke to professionals and they told me, ‘by the time you black people present [your symptoms] you’re dead, because it’s too late.’ We’re too busy covering it up and not telling anyone,” she says. “That’s why I’m raising awareness, because if we don’t do it, nobody’s going to do it for us.”

Before launching Black Women Rising, Leanne discovered a statement from NHS England’s Chief executive, Simon Stevens: “BME patients are less likely to give feedback about treatment, making it difficult for the NHS to identify areas where care can be improved,” it said.

“We shouldn’t keep quiet because they say we don’t give feedback – they do surveys, we don’t answer – so how would they meet our needs if we don’t give feedback. Everyone reacts differently to the drugs and we need to speak about this. Some of the women have found their complexions changed colour because of the drugs, it needs to be discussed. We’re not reporting it to the people who are in charge of our care, so they can’t do anything. That’s where the feedback is so vital and that’s where we falter.”

The problem is, many women don’t have a good experience, don’t feel listened to and are keen to move on quickly. “Cancer affected me financially,” Leanne admits, “I’m a self-employed person and I couldn’t do my job,” she says. “I remember being given a voucher for a free wig – I’d looked them up. A nice one can be £300, £400, £500 – and I was so excited, it was like a weight off of me. When I turned up, there was a big catalogue and at the back there were only a few options for ethnic women. The woman helping said, ‘oh yeah we don’t have any of the black wigs left.’”

It’s these things that make black women feel like an afterthought. Likewise the psychological support offered afterwards. “There was none. I was told to look it up for myself and do the research. When I finally found a support group and went, I was asked if I was there to meet my mum. I had to explain that, no, I’d just been through cancer. I was the only black person there.”

Undeniably, the experience of black women going through cancer is being largely ignored. Leanne has worked to change this. Black Women Rising is a grassroots support group directly helping the women who need it. Women who, otherwise, may not have felt comfortable speaking to professionals in white jackets who don’t take the time to properly listen and understand.

She’s even offered to help wider organisations by raising the issues faced by the black community. “Many cancer charities were reluctant to work with me and for some of the ones that do, I felt like the token black woman. A lot of times, the experience hasn’t been very nice.” Remember, Leanne is still recovering from breast cancer herself. “Sometimes, I’ve gone home and felt battered and exhausted, but I do it for my community, because I want them to feel represented in the leaflets and websites offering help.”

Leanne speaking at the Black Women Rising support group

Naom Friedman

The sad fact is, even this presents a bias. “I already know that I’m unlikely to get the same support as a white woman who appears on the same page,” Leanne confides. While others Go-Fund Me or Just Giving pages take off, Leanne’s has remained stagnant. “No-one was donating. I had maybe a hundred quid to do everything. At the start of the year, it really shook me, I honestly nearly gave up the whole thing because no-one was interested in listening or helping,” she says.

“Do you know, a big brand approached me and pledged a donation, which felt like a turning point. I had another operation for my cancer in January, so I hired an assistant to help me because I knew that the money was coming.” But the money never came from the brand so maybe they changed their mind. “I paid my assistant out of my own pocket,” Leanne tells me, emotionally.

The problem is, the message still quite clearly isn’t getting through to people. “We need storytelling, we need our voices to be heard,” says Leanne. As for non-black allies, “we need people to listen,” she says. Listen and check your privilege. Accept that the system has been weighted to favour white people for generations and we need to level the playing field.

It’s a big job – it’ll take unravelling entrenched, systemic and institutionalised bias, but you can start with yourself. Educating yourself and others around you. Use your platforms and your privilege to amplify the black experience. And, you could also put your money where your mouth is.

If you’d like to donate, or offer your support to Black Women Rising, contact Leanne at foundation@leannepero.com