Tom Zoellner is a tenured Professor of English at Chapman University, the author of numerous distinguished works of non-fiction, and an editor-at-large of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Professor Zoellner has graciously consented to briefly withdraw his critical gaze from high art and cast an eye for SPIN at pop and rock lyrics.

“Don’t you hear that?” you might demand of a friend about a song you love. “That…feeling.”

“Um, no,” they may well say. ”This song sucks.”

Listening to music is a subjective experience. The fertilizer of tones and lyrics makes odd and distinct flowers blossom in the listener’s mind. No two people will have the same internal reaction.

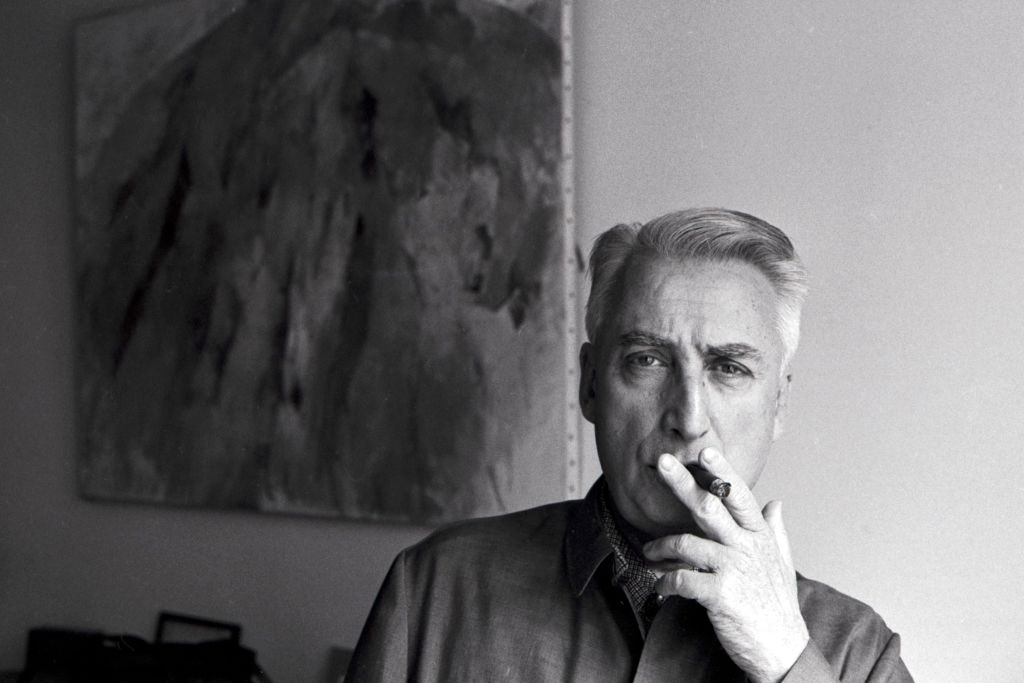

We would do well to remember what Roland Barthes said about literature—that it has no objective properties; it’s a dead and sterile shell that requires a reader to bring their own sensibilities to the page for it to come to life and yield meaning.

There is no “right” way to interpret a poem or a novel. The composer Igor Stravinsky took this “reader response theory” into the concert hall when he proclaimed in 1936 that almost all music “is essentially powerless to express anything at all, whether a feeling, an attitude of mind, a psychological mood, a phenomenon of nature, etc.”

In other words, you might think your favorite song is “about” something specific, even possessing an inalienable meaning that the artist has explicitly said was the intention. But Stravinsky says, “this is only an illusion and not a reality.” It’s only a jumble of sound, and it’s up to you to decide what it means.

Allow the professor to tell a story from his 1970s childhood, when consumer choices were significantly more limited. Pop music was channeled through the hierarchy of recording labels and radio stations, And in Phoenix, you got your “adult contemporary” from KOY-AM, a reliably pleasant and unthreatening stream of soft pop hits.

In January of 1978, when your professor was in 5th grade and being driven to soccer practice by his mother, the song “Baby Come Back” by a band named Player was omnipresent. It was #1 on the Billboard charts for three weeks.

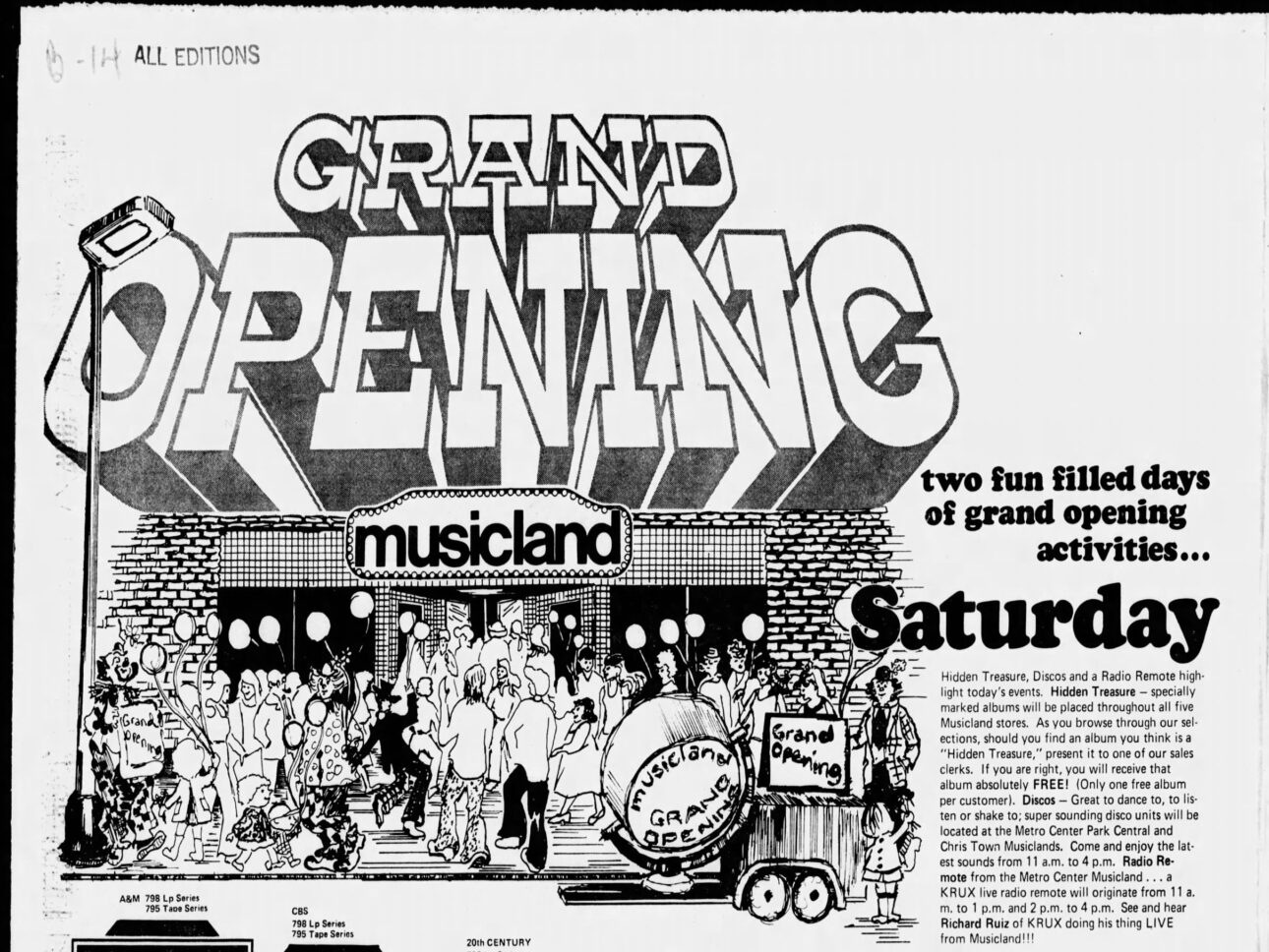

I liked it. So much so that I used allowance money to buy the 45 record from Musicland in the Metro Center mall (later brought to global fame by Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure but in recent weeks demolished). It was my first ever music purchase. It spoke to me about the mysterious world of adults and the things they did that I couldn’t quite understand, but wanted to, and the dangerous idea of love: hazy images of skyscrapers, rainy streets, and long bluesy nights of kissing. And as I listened more carefully as I got older, I came to think of it as not just a good song, but the perfect pop song; a beau ideal of the genre.

Later, in graduate school, when I learned of the scientific reading methods of the Russian Formalist movement, I thought of “Baby Come Back.” It was a flawlessly executed triple axel, an impeccable construction: hook, verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, guitar solo, reprise, outre. No Roman arch was more solidly constructed.

And the subject: could it be any more classic? A man’s lady has left him, and he mourns. Here lies the key subject of the blues, the ancestor of rock and roll.

Baby come back, any kind of fool could see

There was something in everything about you

Baby come back, yeah, you can blame it all on me

I was wrong, and I just can’t live without you

Plain vanilla it may have been, but vanilla is a damn good flavor of ice cream. This was high-quality middlebrow art. That neat juxtaposition of “something” and “everything.” A smarty-pants reference to “forced bravado” to hide sadness. Even that jive-lite word “fool,” perfectly on-brand for the era.

There was even a hidden meaning. Near the end of the last chorus, the instruments go respectfully silent as the narrator makes his confession a capella.

I was wrong, and I just can’t live…

He does not finish the sentence. After an ominous half-second of silence, the guitar solo crashes in. We are left with the implication that he “just can’t live,” a far more dire state of mind than the conditional “just can’t live without you.”

He has been contemplating taking his own life.

As the years went on, and “Baby Come Back” remained on adult contemporary playlists that gradually—in the sneaky incremental way of graying hair—slid into oldies programming and, more recently, the retro-categorization of Yacht Rock, I began to draw even more meta-meanings from this song.

Thanks to the psychosis of the music industry, which has the attention span of a goldfish, the band Player never again climbed the sales heights (though the modest airplay of a follow up song called “This Time I’m In It For Love” saved them from the ignominy of being a One Hit Wonder).

Why did they disappear? Could the members have, in their forced retirement, seen their megahit as bearing a new meaning: Success, come back?

I thought so much about this scenario as a kid that I resolved if I ever became a writer, I would try to do a story for a national music publication about what happened to Player, perhaps as a symbol for how the recording industry chews up and spits out its hitmakers, much in the way of an icy-hearted lover that a band like Player might sing about. SPIN magazine has now given me that opportunity, and so I wondered if I should reach out to the original co-writer, Peter Beckett, the lead singer of Player, who now lives in Seattle.

By doing this, however, I would violate a key precept of Reader Response Theory literary criticism, which holds that the intention of the artist doesn’t mean anything, and nor does their personal story. Back in the 1930s, the New Critics called this idea the “biographical fallacy.”

Yet here was a chance to talk with a man whose three-minute ode to a lost love had shaped my childhood views of what it meant to have a relationship as a young adult: brooding, longing, confusion, romantic melancholy, bursts of passion, minor keys throughout (not far off from the truth, actually).

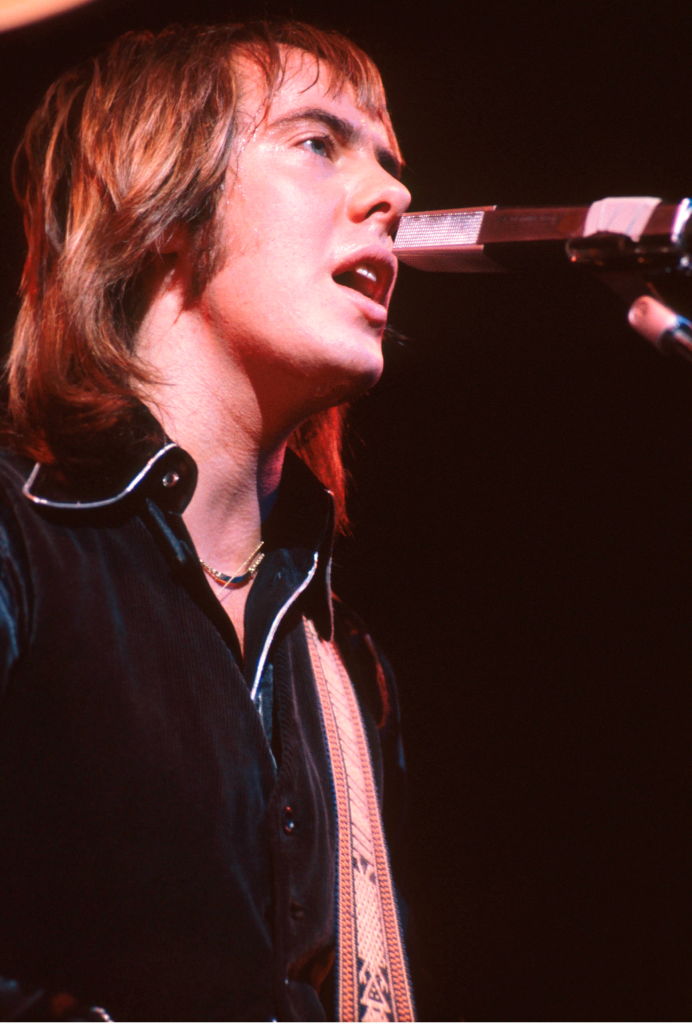

So I sent the emailed request, and within the week, I was on the phone with Beckett, an affable and humorous guy, originally from Liverpool. He told me the story of the song’s origin, a story he’s told for four decades.

In 1974, he was singing backup for a UK group called Paladin and his ambitious bandmate Steve Kipner told him one day: “Pack your bags, you’re going to L.A.” Beckett moved with his then-wife to a cheap apartment where they fought constantly. At some point, Becket went to a fancy Hollywood party where everyone else had been told to wear white. He and a longhaired fellow from Texas named J.C. Crowley were the only misinformed guests wearing jeans, so they naturally started talking. Then they started playing jams together in Crowley’s garage, and chose the name “Player” from the credits at the end of a movie that listed the actors as “players.”

Beckett had been doing jobs on the road. He flew back to LAX one day to find that his wife wasn’t there as promised to pick him up. He got a ride back to their apartment to find she had cleaned out all her belongings and gone back to England without telling him. He later served divorce papers on her via a British attorney, and the two never spoke again.

“When something is kind of whisked away from you, you feel a little forlorn,” he told me. “But I forgot about her pretty quick. In retrospect, it was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Crowley had also been recently dumped, and in the jam sessions, they came up with the elements of “Baby Come Back.” It was one of more than a hundred ditties that they put together, and it didn’t seem to be anything special. But when they played it in a shabby ballroom in Hollywood as a live demo for an official of RSO records—then the king of the disco labels—the response to it was suddenly electric. “That one is a hit!” he said. A self-titled album to wrap around it was quickly produced. The discs went out to national radio stations to see what would happen. And then the rocket went up. The day it hit #90 on the charts was the best day of Beckett’s young life. That was a few weeks before it hit #1.

“We didn’t think about that when we were writing it,” he said. “I didn’t know at the time that it was the perfect song. A lightning-in-the-bottle construction. It was just a song from the heart from two guys dealing with breakups.”

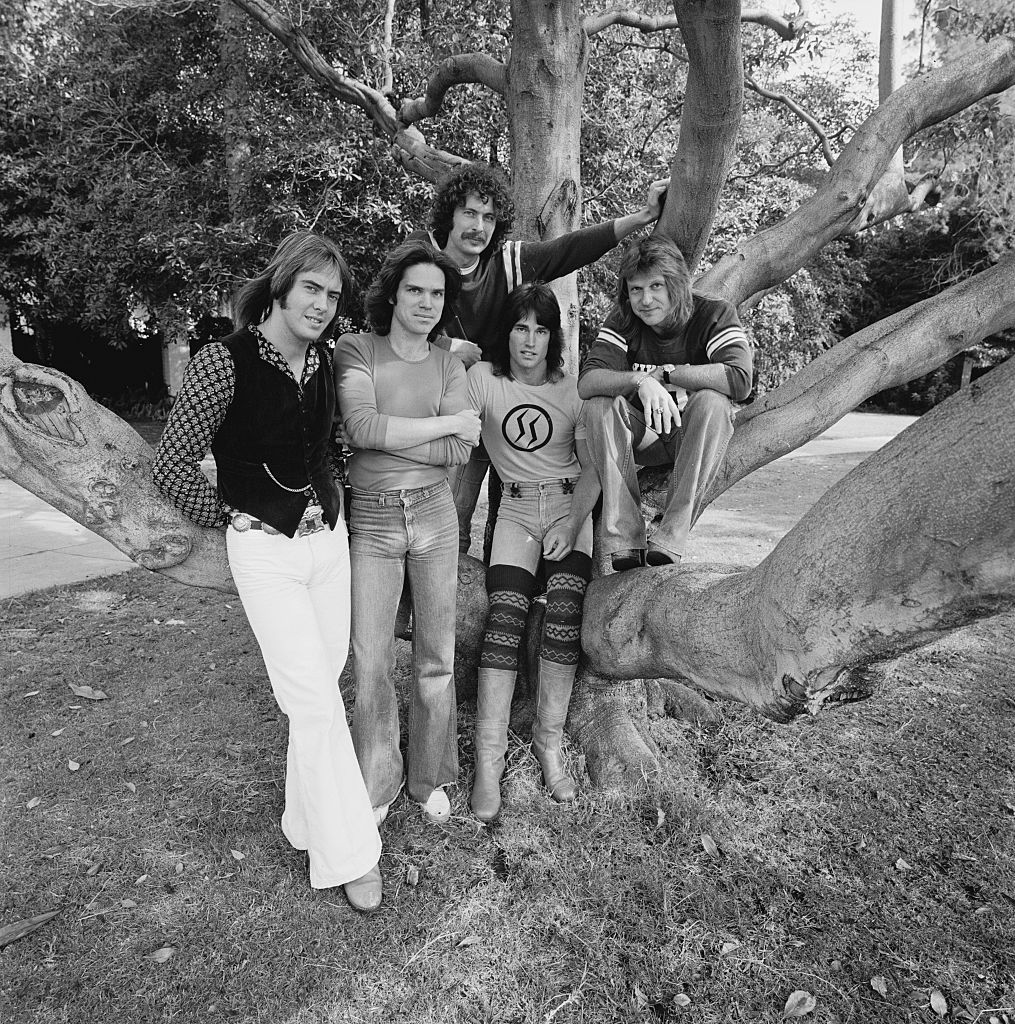

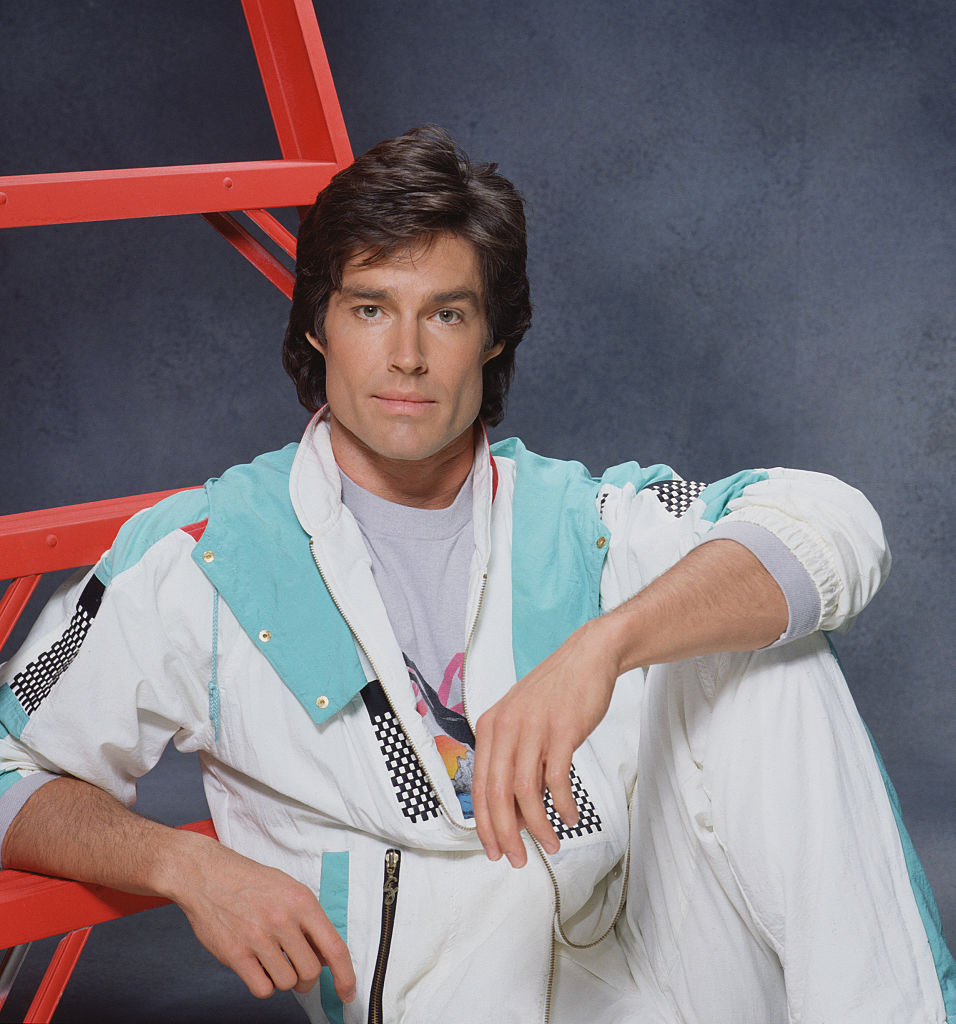

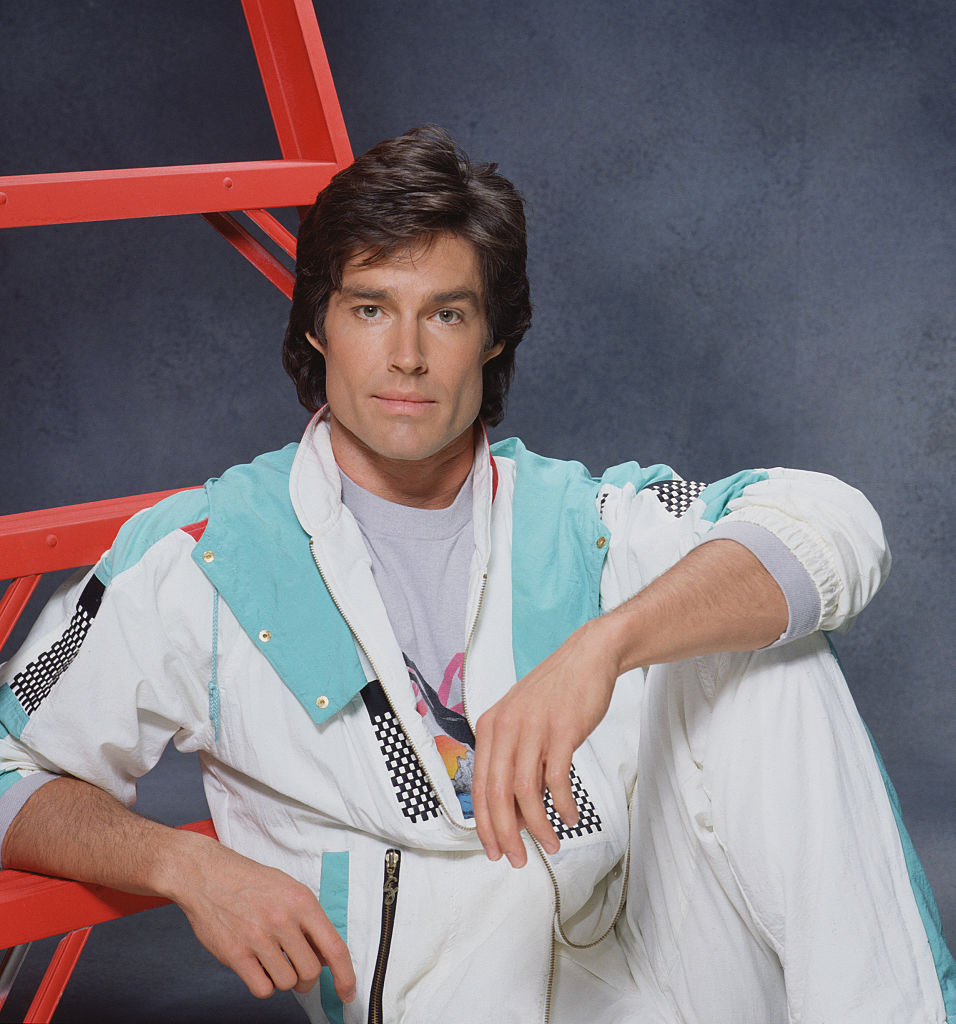

Player got first-class treatment for a few years. They grew their hair long and wore shirts partially unbuttoned. Stadium acts like Eric Clapton, Boz Skaggs and Gino Vanelli asked them to do openers. The band went on Solid Gold. But the iron laws of the recording industry kicked in. You really only get a brief time to be hot before the meat grinder moves on. “Songs are like slices of cheese thrown at the walls,” Beckett told me. “If it sticks, they go for it. If it slides off, forget it.”

A second album did okay, and a third album flopped. Beckett’s ex-wife called RSO’s office, demanding a cut of the profits because she had been the inspiration for the biggest hit (they ignored her). Bassist Ronn Moss left to go be an actor on the soap opera, The Bold and the Beautiful. Band members sued one other for money and naming rights. The creative nucleus fractured. “We don’t love each other anymore,” Becket said.

But Player is still playing. Beckett joined the Little River Band for nine years, and also tours with Ambrosia and sings the old hits (one in particular) under the name Voice of Player. The Yacht Rock renaissance has breathed new life into the embers of a goofy and louche, but somehow innocent, time in American pop history, when songs were mainly about seduction and breakups. “Baby Come Back” still pays a healthy residual check. Altogether, Beckett sounded happy on the phone, hardly wistful. “Because of Yacht Rock, I’m doing more gigs today than I ever wanted to do,” he said. “I can do this as long as my body holds out.”

I asked Beckett about my suspicion that the break in the chorus was the narrator hinting at suicide. “No,” he said flatly. “I drink too much wine to be suicidal.” (This serves me right for violating the Biographical Fallacy).

Did he ever feel wistful about the song itself? What of the double-meaning I had ascribed to it?

“Well, there was this one time when I bounced a check at Ralphs,” he said, referring to the L.A. grocery chain. “I started arguing with the cashier about it, and then the song came on the music channel they were playing in the store.”

I was glad I talked to Beckett; he was a skilled raconteur and honest about the road he had traveled. It was indeed a thrill to interact with someone whose writing had made such a deep impression on me, even if it was packaged in a wrapping of soft pop cheese. But does learning the mundane origins of my favorite childhood song change my reaction to it? I would like to think not. I can still see those rainy streets as in a half-forgotten dream and feel that unnamable something when I listen, the notes lifting it into a different arena. On an intellectual level, I will always defend the view that when it comes to a Platonic ideal form of pop songs, this one comes as close to a divine model as any ever written.

The magic of art lies in its transference. The creator says and does a thing, huffs it into a balloon, if you like, and loses total control of it when he sets it aloft for others to gaze upon. He may never say, Baby Come Back.