Today is the 60th Anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom a.k.a. The March on Washington. While shortening the title makes sense for conversation and headlines, we lose something important to the 250,000+ people who attended and millions who supported nationwide. This 1963 show of action was as much about freedom as it was a demand for more equitable labor standards and federal jobs programs.

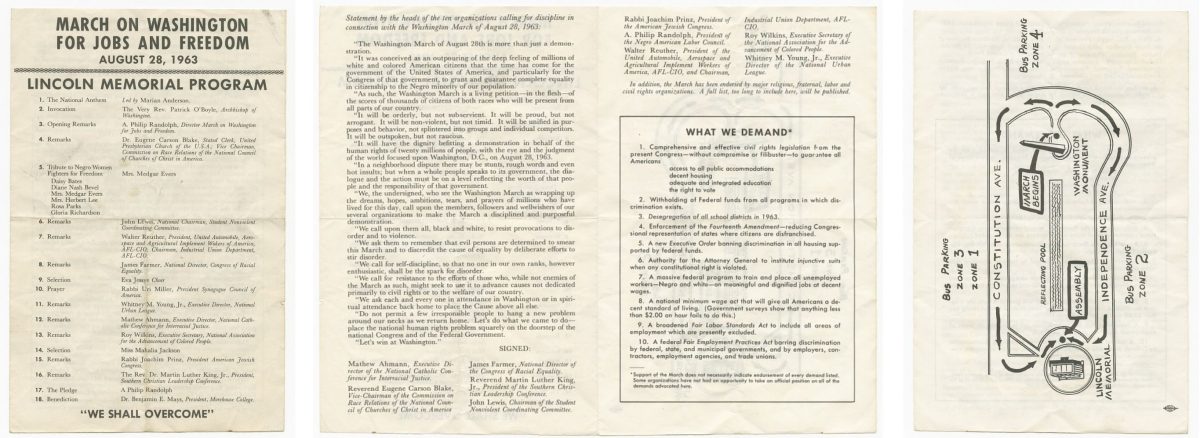

Everyone involved understood that addressing labor needs was vital to anti-racism. In the pamphlet handed out to attendees, four of the ten demands directly addressed issues in labor. Additionally, another four addressed labor concerns indirectly by focusing on education and voting. These demands include:

- Immediate and filibuster-proof Civil Rights legislation regarding public accommodations, housing, integrated education, and voting

- No federal funds for programs with discrimination

- Complete desegregation (this comes nine years after it was already outlawed without enforcement)

- Enforcement of the 14th Amendment

- Executive Order banning housing discrimination in projects supported by federal funds

- Allow Attorney General power to go after suits regarding constitutional rights infringement

- “Massive” federal jobs and training programs for all people focused on dignified work and wages

- National minimum wage ($20 by today’s standards)

- Broaden Fair Labor Standards Act to prevent exceptions

- Barring employment discrimination at all levels of government—including contractors, agencies, and unions

(Anything in parathesis is my note.)

Known as “The Big Six” the march was primarily organized by A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Whitney Young, and James Farmer. Three other key figures include the marches’ chief architect Bayard Rustin, “Godmother of the Civil Rights” Dorthy Height, and United Auto Workers president, Walter Reuther. Having a group of people with a background in labor action influenced this list and the message of the 1963 march.

Connecting Labor History to Civil Rights history

Even the reason this didn’t happen sooner was in part because of labor-related issues. Randolph and Rustin planned on executing this march back in the 1940s. However, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called in Randolph and asked him to call it off in favor of a watered-down executive order. As Rustin and Randolph anticipated, limiting civil rights laws and enforcement to one industry was not enough. Twenty years later, President John Kennedy tried to dissuade the 1963 organizers, too. Thankfully, they marched on anyway.

Despite the U.S.’s riches gained from stolen land and chattel slavery, the conversation of Black labor often gets limited to maybe a footnote. W.E.B. DuBois might get a nod, but rarely a Frank Crosswaith, Fannie Lou Hamer, or Richard Wright. Within 20 years of slavery’s abolition (kinda), the U.S. had a major labor movement through the beginning of WW2. Through action and sometimes bloodshed, many Americans pushed for massive labor reform despite police and capitalist pushback. This includes standards like the 40-hour work week and child labor protections. Lots of this 1880-1930s rallying came from European immigrants and people of color.

Instead of focusing on the labor action of unionists, socialists, and communists our media and education system highlights presidents signing flimsy protections. Protections that—like the ten demands show—aren’t always enforced. All of this was going on alongside the multiple wars, racial terrorism, and in the midst of the Red Scare. This makes the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom an even bigger feat that’s worth celebrating. The focus was Black freedom underpinned by labor protections and economic support for all Americans.

(featured image: National Museum of African American History and Culture/Smithsonian)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]