If you follow my work, you know how I feel about Ted Lasso: it used to be one of my favorite shows, but these days I find it unwatchable. What used to be sweet is now cloying and sentimental. What used to be funny is now embarrassing to sit through.

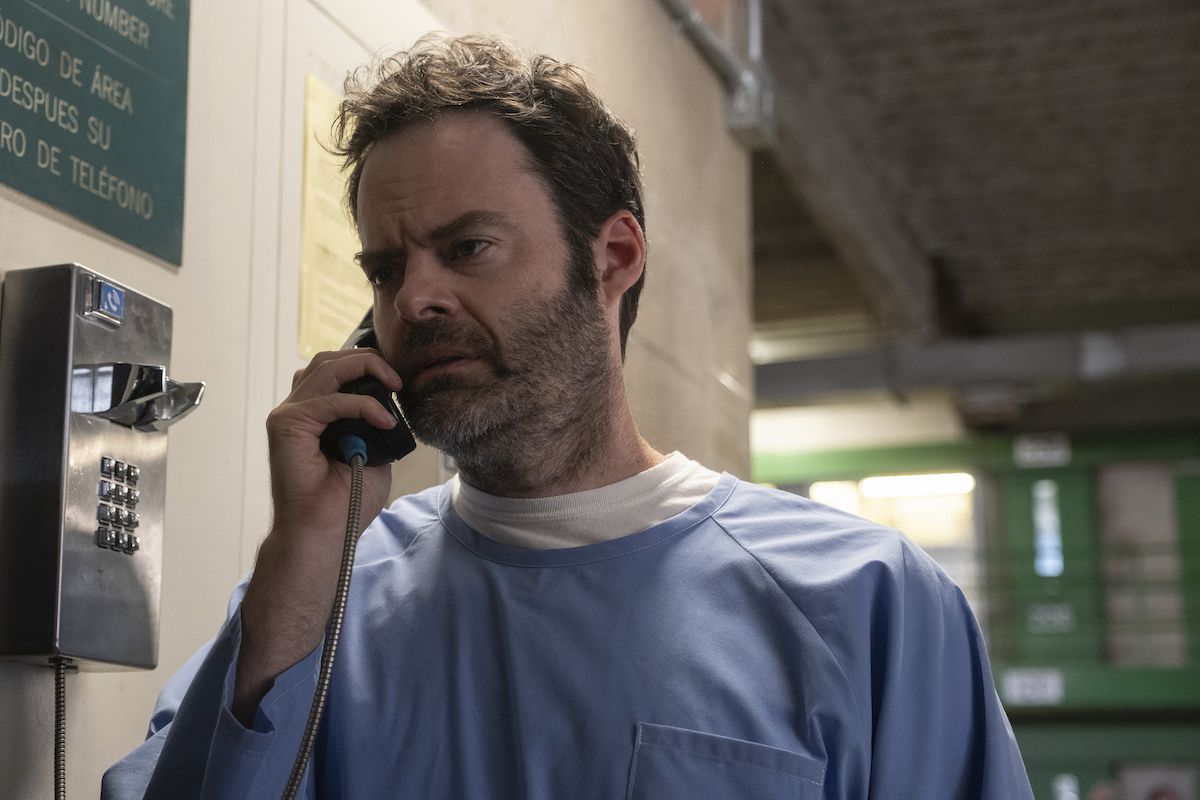

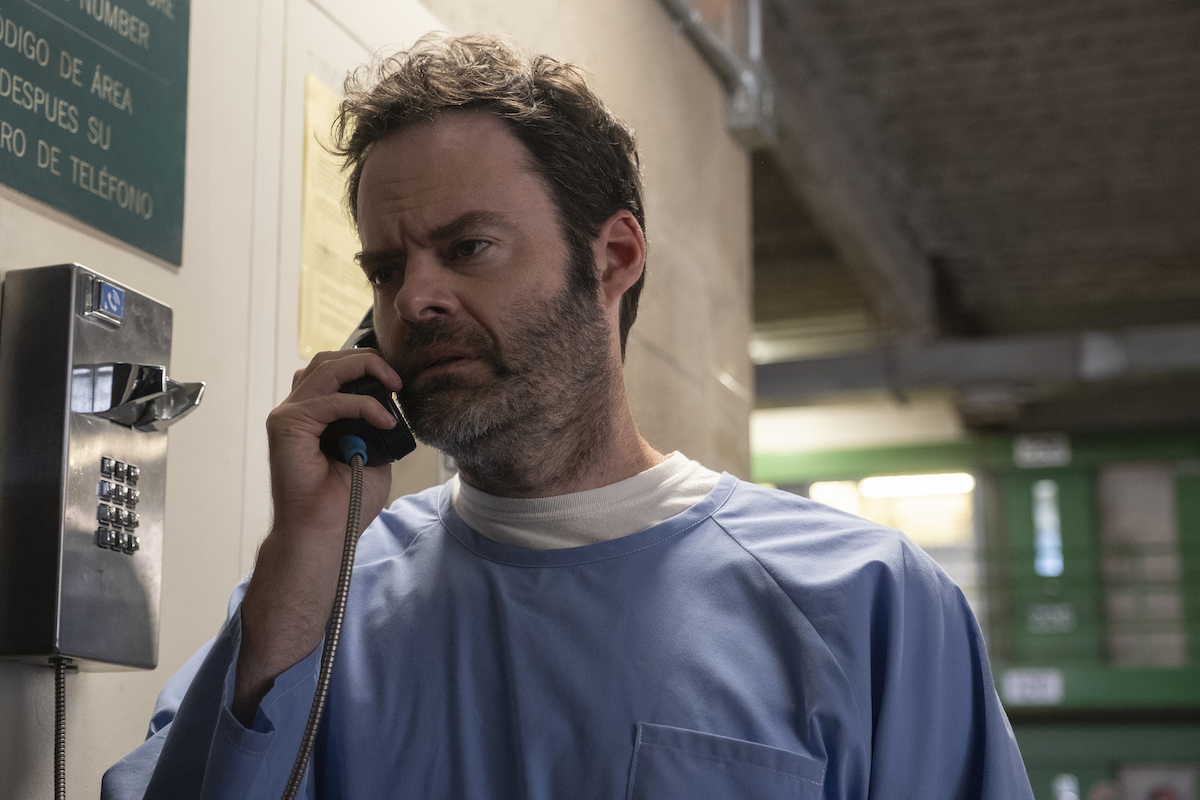

Meanwhile, Barry—also rapidly approaching its series finale—is just as compelling as it was in season 1. All the threads the show has been spinning are coming together, and I’m just as invested in the story as I was when Barry actually thought he might become an actor.

At a glance, the two shows seem very different. They have some surprising commonalities, though. Both center on a central character whose personality has ripple effects on everyone around him. In Ted’s case, those effects are positive, as everyone learns about kindness and compassion. In Barry’s case, they’re corrosive, as everyone is sucked into an abyss of violence and paranoia. Ted’s influence slowly helps Rebecca get over her toxic ex Rupert; Barry’s crimes make Sally give up her dream of acting. It’s likely that Ted will be celebrated as a mentor and friend when Ted Lasso ends, while fans are speculating that Barry will eat it in the series finale. Either way, though, both shows start with one compelling lead and then work their way outward, building up worlds populated by rich, complex characters.

So why has Barry continued to soar, while Ted Lasso is crashing and burning?

In a recent article for Next Best Picture, Brendan Hodges breaks down why so much of it comes down to timing.

We are in a time where every other series seems to take a “super-size-me” approach to episode length, doing in three or four scenes (or even multiple episodes) what they should do in one or two. “Barry,” by contrast, is a rare example of clockwork storytelling, where even as the plot accelerates and the tone darkens, it has a powerful narrative economy where every scene still counts.

Indeed, Barry’s best narrative choices are often the ones with the least amount of screen time. The time jump in season 3, which skips forward eight years, may go down in TV history as one of the most daring—and successful—storytelling moves ever. We don’t need to be spoon-fed the fact that Sally and Barry ran away together. The moment we see them in their desolate house, looking after their troubled son, we get all the information we need. The narrative trusts us enough to let us get our bearings and catch up.

Compare that episode with a Ted Lasso scene I’ve already complained about: the “Hey Jude” scene, in which Beard painstakingly explains to Ted’s son Henry that divorce might suck, but Henry’s parents still love him. Except everyone already knew that. There’s nothing interesting or groundbreaking about Beard’s speech at all. He’s just repeating what Ted, Melissa, and every other adult in Henry’s life has probably already told him. Imagine how much better and more honest that scene would have been if it had taken six seconds instead of six minutes—if, say, Beard had communicated something meaningful to Henry through a single line, instead of an entire monologue consisting of nothing but clichés and clumsily appropriated song lyrics.

Because that’s what Ted Lasso used to do! Like Barry, Ted Lasso episodes in seasons 1 and 2 were only half an hour long. Each story was tight and compelling. Every joke landed. Every emotional beat was keen and impactful. Ted Lasso used to be a fantastic show. But then someone decided that in order to be taken seriously, Ted Lasso had to be twice as long.

In fact, every network and streamer now seems to think that length is the key to prestige. I loved Mrs. Davis, but I still tuned out during some of those extended sequences. I tried to watch Dead Ringers, but was bored to tears by the end of the first episode. Longer doesn’t equal better, but TV execs don’t seem to understand that.

Bill Hader understands the power of restraint in storytelling. Here’s hoping that more shows follow Barry‘s lead.

(featured image: Max)

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]