There’s nothing that should seem so revolutionary about Women Talking. In its atmospheric score and desaturated tones, the Best Picture nominee is designed to be as unobtrusive as the Mennonite women it portrays, each of them conditioned to be quiet, gentle, and subservient, even when their natural temperaments grate against that training. In the film—adapted from Miriam Toews’ book of the same name, which is based on a true story—that subservience is expected to extend into the aftermath of being raped by their husbands, sons, and brothers, several of whom have been arrested by the time the film begins. In the absence of the rest of the colony’s men, who’ve left town to bail the rapists out of jail, the women must decide what comes next. Who are they, in the absence of their supposed superiors? What is the godly thing to do: Stay and fight? Leave? Pretend the violence never happened, or that it will ever stop?

In these moments of fight-or-flight, a group of women gather in a hay loft for hours of sometimes heated discussion. In the film, these women are played by a stellar cast that includes Rooney Mara, Claire Foy, Jessie Buckley, Sheila McCarthy, Judith Ivey, Kate Hallett, Liv McNeil, and Michelle McLeod. With them is a single man, the boys’ schoolteacher and the book’s narrator: the nervous but admiring August Epp (Ben Whishaw). Because none of them have been taught how to read or write, the women depend on August to take the notes of their meetings, and to record for posterity all that transpires between them. In the din of the barn, they lay out the conundrum before them, debating the nature of forgiveness, the lingering claws of trauma, their indirect responsibility in the violence inflicted upon their daughters, and whether escape—let alone change—is possible after so many years.

There is nothing precisely new about this conversation, which means it’s tempting for audiences to lump Women Talking in with a dozen other post-#MeToo films, stick it with the appropriate accolades, and call it good. But that would be a profound missed opportunity, not to mention a misreading of the material. Women Talking is revolutionary not in its subject matter, but in its focus: nothing more and nothing less than the words shared between survivors.

During an early December 2022 press conference, Frances McDormand—who optioned rights to the book after its 2018 release—pinpointed the importance of this distinction. “When I read the book,” she says, “I realized this was the kind of atmosphere, this was the kind of way I wanted to talk about what I was feeling: in a group of women with nuance, with a sense of humor, with a sense of community, with a sense of urgency, but with a real thoughtful milieu. I mean, we all think of the hay loft now as a very sacred place. It’s like the hay loft is the capital H place where we now go.”

The problem with a hay loft, of course, is that it isn’t exactly visually stupendous, nor is the average audience used to the film version of what a television director might call a “bottle episode”—which is spent almost entirely on one set. Even some of the film’s acclaimed cast members feared Women Talking’s commitment to the hay loft might be an overreach. In an interview ahead of the film’s release, McCarthy—who plays the gentle matriarch Greta—told me, “In this age of short attention spans, I was concerned that people wouldn’t be patient enough to listen to us.” She was thrilled, she says, to be “wrong.”

But it was producer Dede Gardner who pointed out the internalized bias and underlying problem behind these initial concerns. During the press conference, she laid out what, perhaps, should have already been obvious: “If there can be 12 Angry Men, there can be eight women in a hay loft.”

It’s not surprising, then, that filming Women Talking was an experience similarly profound in its simplicity. Sure, the scenes were demanding—one of Foy’s monologues called for somewhere around 120 different takes—and yet the results never came out forced. “We were doing 10-page scenes 150 times and they were full energy, full tilt, full engagement the whole time,” Foy tells me. “You have to have a whole toolbox of stuff that you can rely on, basically, that is your backup in case you get to a point where you’re exhausted, you’re tired, you’re hungry. … I think there were definitely days where we were going a bit mad.”

The actors, who made use of an on-set therapist, speak of their time filming in Toronto with solemn, dreamlike adjectives, giving credence to what McCarthy says was “a hymn-like quality to the entire experience.” The mood was surreal; the effort involved, Ivey tells me, was indeed “Olympian.”

“You didn’t want to let anybody down,” she says. “That was always my feeling: ‘I need to give it 110 percent every time because I want to be there for [the cast] the way they were there for me.’ And that never wavered. It was constant throughout the process.”

In a separate interview, Whishaw adds that the understanding amongst the actors in the hay loft never needed to be vocalized in order for it to be felt. “It was beautiful in that it was—‘respectful’ is the word I keep thinking of,” he says. “Nothing needed to be said too much.” Everyone acknowledged the weight of the material. Everyone grasped the seriousness of the task at hand. Still, no one tried to make it more than what it was. And perhaps more than anything, everyone trusted director Sarah Polley.

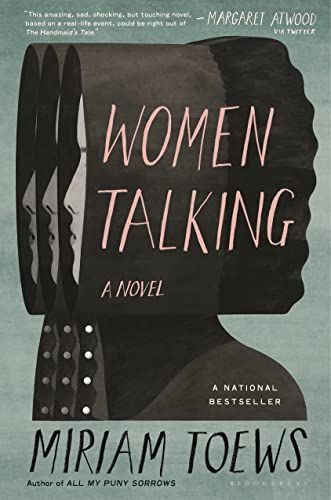

Polley, a Canadian filmmaker and former child actress who directed her first feature film at the age of 27, is a renowned name in Hollywood. She wrote the script for Women Talking herself—without the guaranteed backing of a studio—and helped assemble a cast that would feel, she told journalists at the December press conference, like “a theater troupe that you’d wanna travel with.” Given that Polley’s an enormous fan of Toews’ book, her fidelity to the source material is felt in almost every frame, each of which study the Mennonite women without ever misrepresenting or judging them. The actors say they felt the same gentle, scholarly approach from Polley when it came to their own work on set. Hallett, who plays the young narrator Autje, put it this way: “[Polley] was always making it very clear that if you ever needed to take a second, it doesn’t matter if we were on a tight schedule. ‘You take a second and we will wait until you are ready to come back.’” In this way, Polley echoed the sincerity of Toews in representing these hurting women with dignity and grace.

Still, it’s in two essential changes from the book that Polley’s genius is most felt. One is obvious from the film’s beginning. The other isn’t clear until the end.

In the book, Toews’ narrator is August. As the only man in the hay loft, he’s the only one with the skills to write down what takes place, and so the book is drawn from his perspective as an outsider-turned-insider. And, for the film, Polley attempted to replicate this effect, even having Whishaw record the entire script’s worth of voiceover narration before she realized something was missing. “Suddenly, you have the immediacy of and the intimacy of sound in your ear and images in front of you,” she told the press conference audience. “Suddenly, you needed the voice of a women who had gone through one of the attacks in a way that you didn’t need [it] in the novel.”

So Polley turned to 18-year-old Hallett, whom she asked to try recording a few voiceover lines on her smartphone, audio quality be damned. Satisfied even with these preliminary results, she brought Hallett into the studio months into post-production, where the young actress recorded the narration that ultimately made its way into the film. Presented as a letter to the child of Rooney Mara’s Ona, as yet unborn and unseen until Polley’s very last shot, the words ground the entire film in the innocence, violation, and hope of the hay loft’s youngest member. “Your story will be different than ours,” Hallett’s Autje says, in a voice so determined it’s easy to forget it belongs to a child.

“I think [Polley and the crew] just felt very drawn to [the narrator] being the youngest person in the room,” Hallett tells me. “Because it’s such a different perspective from what Ben [Whishaw] would’ve had and what, I think, a lot of the women would’ve had.”

This choice is made all the more significant thanks to Polley’s second change from the book: She depicts the women leaving the colony not from August’s faraway gaze, but rather in intimate close-up. The audience sees the expressions on each character’s face as she leaves the only home she’s ever known for an unsecured, unknowable future. These women have no map. They have no capital. They don’t even have evidence that men in the outside world won’t hurt them. They have only the extraordinary, baffling hope that, beyond the horizon, something better than the past must be possible. The scene purposefully evokes the Old Testament exodus, echoed from an earlier line of Greta’s: “We are leaving because our faith is stronger than the rules. Bigger than our life.”

Watching Women Talking feels as though it should not seem so remarkable. A group of women argue, laugh, and cry in a hay loft. They pack their things, and they leave. That amounts to the bulk of the film’s story and yet, as Foy says, “Watching it, I’m like, ‘This is new. There’s something new happening here. A boundary is being crossed.’”

In a separate interview, McLeod—who plays the panic-stricken Mejal—told me she agrees with this sentiment. “When we saw it together at Telluride [Film Festival],” she says, “I realized we were in something that I feel is going to be watched, studied, picked apart, talked about, a conversation starter for years to come.”

In 2023, #MeToo stories are common; that’s the point of the moniker after all. Five years after the hashtag went viral in 2017, it’s easy to feel as though measuring the movement’s impact is a fool’s errand, possibly even a disappointing one. Women Talking is a perfect encapsulation of why that feeling is a lie. An impact does not need to be of a certain degree in magnitude for it to be remarkable. The Best Picture nominee’s existence—the unique manner in which it was designed and created and produced—is a feat nonetheless. Like its characters’ ultimate decision, Women Talking is perhaps an indicator not of what is but of what is possible.

Associate Editor

Lauren Puckett-Pope is an associate editor at ELLE, where she covers film, TV, books and fashion.