My collection of David Bowie books takes up nearly two metres of shelf space in the home office. I’ve read practically everything about him, scoured all the websites, written about him on innumerable occasions, seen him live half a dozen times, collected all the memorabilia, and interviewed him twice. What more was there to learn?

Plenty, it turns out.

Read more:

David Bowie held powerful influence on fashion design (Jan. 11, 2016)

Read More

Brent Morgan, the director behind 2015’s excellent Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, as well as films on The Rolling Stones and Hollywood mogul Robert Evans, takes a different look at Bowie with his new film, Moonage Daydream. I guess it’s a documentary, but it’s more of an immersive experience of who Bowie was and what he accomplished over his career. It runs chronologically like a normal doc (well, sometimes), but it offers perspectives on Bowie in a way unlike I’ve seen before. If you’re looking for a traditional documentary, you’re in the wrong place.

With the blessing of the Bowie estate, Morgan spent many 16-hour days over five years digging through more than five million assets in his archives — apparently, the man was a packrat bordering on being a hoarder — uncovering many things previously unseen: lost concert footage, backstage clips, rare interviews and more. He then found a way to string together an intimate cinematic experience that will have even the most hardcore Bowiephiles cocking their head and going “Wot?”

I spoke to Brett about the film. This interview has been lightly edited for space and clarity.

Alan Cross: Someone once told me this: The more you know about China, the more you realize you don’t know about China. It’s pretty much like that with Bowie, isn’t it?

Brent Morgan: I say this about Bowie: The more you listen, the more you know about yourself.

AC: That’s a really good quote. The Tuesday after Bowie died, I went to an event that featured a book of condolences. And someone had written, “We didn’t know you personally, but your music helped us know ourselves.”

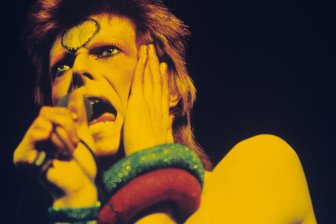

BM: That’s it. And by the way, this is not accidental; it’s by design. There was an interview with photographer Mick Rock three months before Ziggy Stardust came out. Mick says “So David, I understand you have this new album, a space-age concept album.” And David said, “Ah, no, man. It’s a gas! I just used the words ‘space-age’ and ‘raygun’ and that’s it! They’re going to fill in the blanks.” From that point, he understood the point of keeping things vague and to allow us to create a relationship between the spectator and the artist. We are constantly projecting onto him and then reflecting back to us.

It never even entered my mind to do a biography on David Jones [Bowie’s real name]. I was interested in creating an experience that was as mysterious, as enigmatic, as inspiring, as life-affirming as I get from David. It’s very important to draw this distinction. From the moment I started this film, I wonder how I was going to set the audience up to show that it’s not a biography. Normally, these projects are a concert film or a biographical documentary. That’s the genre. There’s no other inroad. And genre is so critical. Because if you go to a comedy thinking that you’re seeing a tragedy, you’re going to have a real hard time with it.

There aren’t really any “facts” in this film. One of my rules of filmmaking is if you can read it in a book, I don’t need to present it in a film. My films are designed to be everything you can’t get in a book, which is something intangible. It’s almost like wine and extracting juice from the grape.

AC: The movie is really … trippy. We do go through Bowie’s life, but what we see and hear is a portrayal of Bowie that I don’t think we’ve seen before. So what is it?

BM: It’s the tao of Bowie. It’s an immersive experience. My entry point was seeing a Pink Floyd Laserium show at the Griffith Park Planetarium in Los Angeles. When I was in high school, every weekend we’d drop acid, put our heads back, and watch the show. And to this day, it’s one of the greatest immersive experiences. I’ve always loved cinema. I love being swallowed by cinema. I love sound and I love to feel sound more than I like to hear it, which is something I’m constantly telling sound designers.

The opportunity to take an IMAX theatre, which has the best sound available on Earth, far better than any concert, to take the stems and re-appropriate them so that it seems that we’re hearing the music for the first time, was the starting point. The goal was an immersive, sublime experience.

I had that idea before anyone was doing Bowie. This thing was birthed coming out of Montage of Heck. I thought why do we need the story? Let’s just use the sound system and create everything I love about cinema. The mystery [of Bowie] doesn’t need to be explained.

And then I had a heart attack while I was getting the film prepped. I flatlined for more than a couple of minutes [it was three] and was in a coma for a week. When I came out of that, I was not broken. The first words out of my mouth to the surgeons were “I gotta be on set on Monday. I’m directing a very important pilot for Marvel.” And he’s like, “You’re not going anywhere.” I pulled the plugs out. I mean, I was insane. It was about four months later when I finished that show and was getting into Bowie I realized that what he was offering me was not only a road to recovery for myself but a roadmap on how to lead a fulfilling and successful life for all of us. It became all about having the audience as they leave ask themselves these questions that Bowie is positing to us. “Are we making the most of each day and how do you go about that?”

What was Bowie’s secret? When he was comfortable, he’d switch things around. Being comfortable was the worst possible position for him to be in. One of the things that I think separates David from just about every major cultural icon of my lifetime … I mean, no one wants to risk not having an audience. Bowie, as he says, rejects virtuosity. That idea, to me, is singular to David. I don’t know any other artist who’s that willing to risk their audience to fill a creative itch. I was able to draw so much inspiration from that and I think audiences will as well.

AC: He was not a guy who was not afraid to rip it up and start again. The film also underscores how deep of a thinker Bowie was.

BM: He was the most well-read, thoughtful, philosophical artist of our lifetime. I don’t think he was the greatest singer, I don’t think he was the greatest actor, I don’t think he was the greatest dancer, I don’t think he was the greatest painter. But he put 100 per cent of himself into his work.

[Even after the highs of Let’s Dance and his audience turned away], I don’t think he really cared. He was making music from a different perspective. He had a home finally and made some beautiful music in the later part of his life.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with Q107 and 102.1 the Edge and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

© 2022 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.