When 16-year-old Yamilet came out, she lost her best friend and entire social circle. Hoping to start over, she decides to play the role of a super-straight girl in her new environment: a Catholic high school.

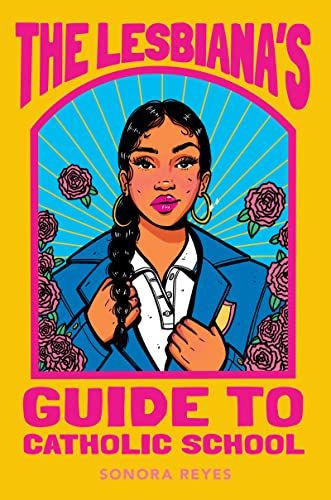

Sonora Reyes’ The Lesbiana’s Guide to Catholic School follows Yamilet’s struggles to keep her queerness under wraps, especially when she meets her new crush, a girl named Bo who isn’t afraid to wear rainbow attire and speak out against homophobic teachers. The young adult novel weaves a story of teenage romance with discussions around first-generation pressures, migration, mental health, and growing pains.

Growing up, I didn’t know any stories about queer girls, especially Brown girls. Like Yamilet, I attended a Catholic high school (mine was all-girls while hers is co-ed) where we were required to wear a uniform. On the days we attended mass, which took place in the school’s gym, we had to wear a thicker, more formal skirt and a burgundy blazer. Even though I wore the uniform just like everyone else, I felt immensely out of place, because in those years, I realized I identified as bisexual. Reyes’ novel, then, immediately caught my attention.

Tasked with looking out for her brother, who often got into fights at his old school, Yamilet navigates a new social sphere. She develops a crush on Bo, who challenges the school leaders’ bigoted statements. At one point, a teacher has students practice their debate skills, focusing on whether gay marriage should be legal. Bo makes a point that it’s already legal, before storming out of class; Yamilet, who’s assigned to the opposing group, runs to the bathroom to cry after hearing her classmates argue about why gay people shouldn’t get married. In another scene, Bo speaks up during mass, asking the priest why being queer is sinful, especially when gay marriage is legal; the priest responds that while that might be the case, it’s still wrong in the view of Catholicism.

It takes effort to hide your true identity, and even more energy to stand firm about who you are in a room full of people who don’t consider you worthy. The homophobia Yamilet and her brother Cesar grow up around seeps its way in. While Yamilet doesn’t fully come out at her new school, she silently rages against others’ beliefs. She feels constantly judged by the Catholic community around her, furious that it won’t accept her full, queer self. And when Cesar comes out as bisexual, she’s angry when she realizes this was the root of the “fights” he got into at school.

Yet in some moments (like the debate scene), it’s hard for Yamilet to maintain a strong sense of self. Cesar takes the religious teachings around him to heart, feeling a deep shame about his identity. The two repeatedly search for ways to feel at home in their own skin.

Same-sex marriage wasn’t yet legal during my high school years, though there was definitely talk about it. When I realized I’d fallen for my classmate Nancy*, I didn’t initially think about what it might mean for us to be together in a small, Catholic school. Queerness was seen as wrong and strange, and that judgment hung over us like a quiet fog.

For years, I told myself that because my coming out story didn’t result in physical violence, I shouldn’t overtly publicize my experience. The micro-aggressions, many of which I pushed down, didn’t seem worthy of bringing up, especially as an adult in a straight-passing relationship with a cis man. Even though I believed I didn’t deserve to talk about it, my high school years did wear me down. I can’t remember why, but Nancy often joked that the principal didn’t like us. I was jumpy, forever trying to hide any affection between us. I walked down the hallways knowing that the majority of the students and the adults marked me as an anomaly, as someone unwanted.

In writing Yamilet, Reyes gives us insight into a character trying to figure out her own place at school, in religious circles and, ultimately, in the world. Yamilet is still hurting from the way her best friend, Bianca, cuts her off after finding out about her queerness. I know what that feels like; Nancy told me that girls she previously called friends stopped talking to her when they found out we were dating. And I vaguely remember someone saying that if I hugged them for too long, I might develop a crush on them. I kept turning that comment over and over in my head, until I got down to the core of why it hurt so much—being queer was equated to being othered or an outsider; not a friend or acquaintance, but someone to be avoided.

Yamilet explains it perfectly in the novel: “When I told her I loved her, she made me feel like a leech, like I took advantage of her by being her friend. Like it was only for my benefit,” she says. “It didn’t matter to her that I wasn’t ready to come out until then. The years we spent as best friends didn’t matter because I must have had ulterior motives, and everything I had done now seemed creepy.” I can’t imagine what it would’ve meant to read Reyes’ novel as a teenager, to hear someone put into words the guilt and fear I felt.

Now, as an adult, I’m trying to wrap my head around the idea that books like these are being banned in schools. PEN America reported earlier this year that 33 percent of the books “banned in 86 school districts in 26 states” from July 21 of last year to March 31 of this year “explicitly address LGBTQ themes, or have LGBTQ protagonists or prominent secondary characters.” Approximately 1,145 titles have been banned. The report also states that 41 percent of these books “included protagonists or prominent secondary characters who were people of color.” Reyes’ literary agent tweeted just a few days after the release of The Lesbiana’s Guide to Catholic School that it was already receiving hate. How can a Brown queer girl or Brown non-binary teen see themselves today when these stories are being censored?

Nancy and I broke up and got back together multiple times, mostly when I got too afraid and anxious about the disapproval of the people around me. Our relationship was flawed and we rebelled against our parents sometimes. But it was a kind and loving partnership, even at such a young age. We talked about our nieces and nephews, wished each other luck on homework and tests and competitions. We talked about grief. We exchanged inside jokes and sappy messages on Facebook. I sent her good vibes before band practices. She modeled what true commitment and passion to a creative practice could look like.

It’s heartbreaking, at times, to think about how my teenage self cast this as a shameful relationship. I didn’t have any queer couples to look to; instead, I repeatedly heard religious and personal declarations about how “wrong” it was to be queer.

The shame lingered for years; in college, a friend invited me to visit her hometown during one of our breaks from school. As the date approached, we excitedly made plans and discussed the details. She told me I could just sleep in her bed with her, that there was plenty of room. I hesitated when she told me and came out to her as bi.

“That doesn’t change how I feel about you as a friend at all,” she said. “That doesn’t change anything.”

It was a small gift.

Nancy and I kept in touch after we broke up and I started at a new college. She patiently read my messages about my relationship problems. I confessed that I was too afraid to date women. Dating guys, I told her, was just easier. Not giving myself the space to explore my full self, in the way that Yamilet does, was safer.

In my late twenties, I embraced my queerness more fully and I got louder about it. I felt unapologetic about so many things in life—my decision to live with a partner without marrying first, my multiple tattoos—except for that. In earlier years, I felt like a fraud if I brought up being bi. But as oppressive policies continue to be passed—like a certain bill that prohibits teachers from speaking about gender identity or sexual orientation—it feels wrong to be quiet about it.

The final scenes of Lesbiana’s Guide to Catholic School feel bittersweet because I know not every queer kid gets that type of happy ending. It’s not that Yamilet’s life will never feel difficult again—by the end of the novel, she’s not speaking to her father. But her mom surprises her and Cesar one day with rainbow papel picado and pan dulce.

At an anti-prom party, Yamilet and Bo dance until they fall onto the lawn, and as she settles into the grass with Bo beside her, Yamilet finally lets go. “No more second-guessing. No more double life,” she tells us. I didn’t feel so brave at Yamilet’s age, but in reading Reyes’ writing, I gave my teenage self a little more grace.

*Name changed for privacy

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io