Months after a racial reckoning spanned North America in response to George Floyd’s death, Black Canadian artists say there’s been progress in their field — but there is still a long way to go.

Global News spoke to four emerging members of Toronto’s Black arts community to gauge whether there had been a shift in their industry in the fight against anti-Black racism and the push for more diverse representation.

Here’s what they had to say.

Read more:

Southern Ontario school boards say they’re unable to track complaints of anti-Black racism

Miro Oballa

Miro Oballa is an entertainment and media lawyer who launched a not-for-profit organization called “Advance” last year. The organization launched in response to the George Floyd movement.

The group aims to have Black talent agents and managers represent Black musicians, something that Oballa claims happens more commonly in the U.S. than in Canada.

“I think by not having Black people in senior positions and decision-making roles for Black artists, what’s lost is a preservation of the cultural understanding of some of the values and motivations and things that are driving those artists to create that music,” Oballa said.

He adds that there’s been an early wave of support for his organization, even in its infancy.

“The industry is working with us and they’re taking steps and talking to us — and you can see a lot of change wants to be made.”

Oballa believes the George Floyd movement sparked a dialogue on better representation at managerial levels of Canada’s music industry, but now that needs to move toward action — especially toward training the next generation of Black Canadians in his field.

“There’s an education, a mentorship piece (at Advance), which is about training the next generation of managers and even those artists who handle their own business and entrepreneurs in the industry and give them the skills and the resources for them to succeed.”

Densil McFarlane

Densil McFarlane is the lead guitarist and vocalist for Toronto-based punk rock band, the OBGMs.

He said, as a Black man, navigating a genre that is predominately white can feel “lonely.”

“I made a whole album about being angry because I wasn’t recognized in this space and people would often question why we were in this space. It drives you crazy,” he said. “It makes you feel like you’re doing something wrong.”

McFarlane adds that when his band used to go play at concerts, some people wouldn’t recognize him as the artist who’s about to perform.

“They would think that we were the drug dealers, the in-house drug dealers for the spot,” he said.

“We are trying to break in a space that doesn’t have a lot of people that look like us,” McFarlane added. “They aren’t from where we’re from. They don’t sound like we sound. But that is disheartening, for a person like me that really wants to share the space and thrive in that space too.”

McFarlane feels that there has been a positive shift in Toronto’s rock scene since last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, by allowing himself to have more conversations about race and allowing others in his field to be more open to the dialogue.

“I’ve felt comfortable having conversations about Blackness with people that weren’t Black, because typically when these conversations were had, they would be met with gaslighting or disbelief,” he said.

“I would say it pushed the needle forward, in a lot of different ways that are positive — but there is still a long way to go.”

Read more:

‘We’re sick and tired of it’: Members of Toronto neighbourhood share stories of anti-Black racism

Top5

Top5 is a Toronto-based rapper who gained recognition as a teenager several years ago when Drake posted about him on social media.

The 22-year-old from the Toronto neighbourhood of Lawrence Heights said there’s been a spotlight on Toronto for years now thanks to artists like Drake, Tory Lanez and the Weeknd — but adds that the local Black hip-hop scene also has a negative stigma related to crime and gun violence after the shooting deaths of several prominent rappers in the past few years.

“It’s hard, to be honest, because you don’t want that to happen to you,” he said. “So you’ve got to find the best way to stay out of trouble. It’s almost like if you’re going to make violent music, just know what you’re doing, because it’s just, one day, is going to catch up to you — there’s repercussions to rapping about violence.”

Top5 said local artists write lyrics that include references to violence because it’s what sells — but it’s also what makes many of them, including himself, viewed as polarizing figures in their communities.

“Not all rappers are bad. I’m a good guy,” he told Global News. “I’ve just got to rap about things just to get up in the neighborhood. What you want to hear, I’ve got to rap about.”

He adds the only way to eliminate the violent stigma associated with the local hip-hop scene is to stop rapping about violence — but he adds many musicians worry that that’ll mean fewer people will want to listen to their music.

“So you just change the lyrics and less people get offended that way, reduces the violence,” Top5 said.

“A lot of people rock with you and they really like your music,” he added. “So if you’re going to rap about violence, just know that there are repercussions — but just less rapping about that stuff, if you’re trying to find a way for your family to get out of the neighbourhood and live in a mansion in L.A. — rapping about violence is not the way to get there.”

Read more:

‘It’s not just a fad’: Black-owned businesses lack support months after George Floyd movement

Micah Lindo

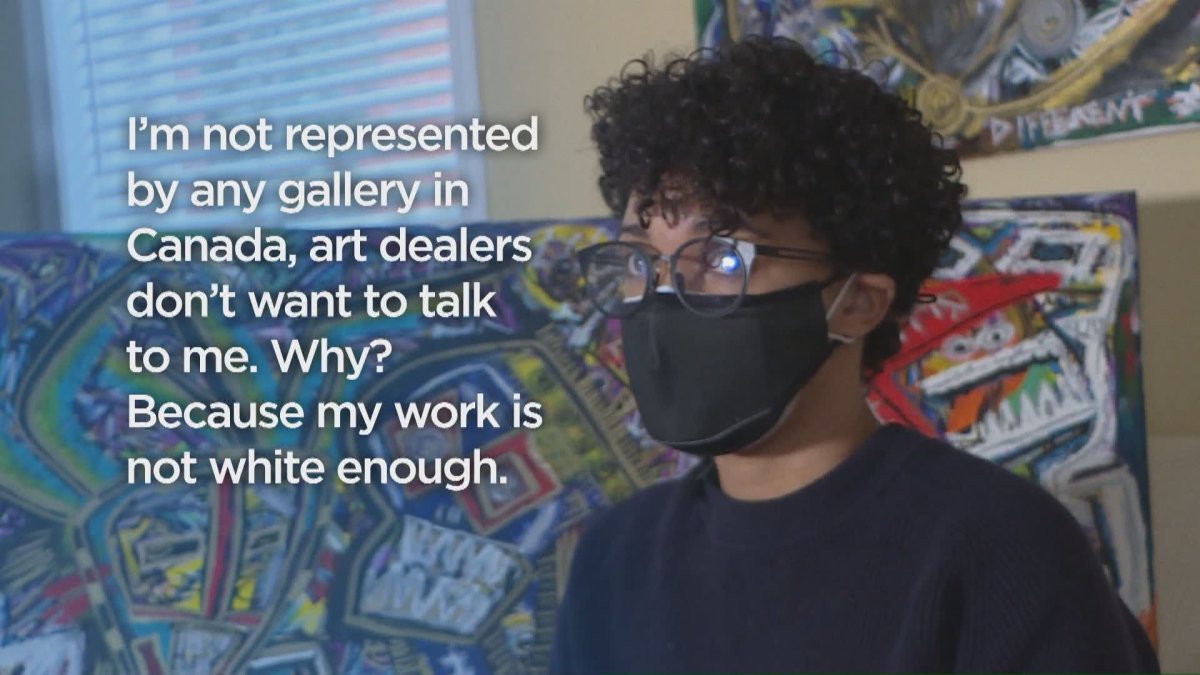

Lindo is a Black painter with autism who identifies as non-binary and said that they face various forms of discrimination within Ontario’s art community because of who they are.

“There’s not very many Black painters to begin with,” they said. “When you think of the old greats, they’re always white people — but that hasn’t really changed in Canada. And as a Black person, if you’re painting from a place inside of you, you can’t paint white.”

Lindo adds that, in their experience, it’s a different in the U.S., where galleries celebrate diversity and different perspectives.

“I’m not represented by any gallery in Canada,” said Lindo, who added they’re represented by a gallery out of New York. “Art dealers (here) don’t want to talk to me because my work is not white enough.”

They add that the George Floyd movement didn’t change much in their field, but it’s not too late for Canadian galleries to be more open to the idea of supporting Black artists by allowing them more solo exhibitions.

“Let us show our art, be open to our experiences. Let us show our art in your galleries, more access, represent us, don’t discriminate.”

— with files from Tiffany Mongu

© 2021 Global News, a division of Corus Entertainment Inc.