Editor’s Note: On Friday September 18th, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away from complications of metastatic pancreatic cancer. The trailblazing cultural, legal, and feminist icon had been on the Supreme Court since 1993, when she was appointed by President Bill Clinton. She became the second female justice on the bench. According to NPR, in the days leading up to her death she dictated a statement to her granddaughter Clara Spera: “My most fervent wish is that I will not be replaced until a new president is installed.”

To memorialize her life, we’re republishing this 2014 interview.

I saw two young women wearing Notorious R.B.G. T-shirts on my way to visit Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her chambers. The 81-year-old associate justice, who was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Clinton in 1993, is portrayed by her many fans as a tough-talking, swaggering gangster. She’s developed this reputation, in part, because during the past five years, she’s written more notable dissents than any other justice. When the court decided against Lilly Ledbetter—a tire-factory manager paid significantly less than men in the same position—because she sued too late, Justice Ginsburg dissented. When the court ruled to invalidate a section of the Voting Rights Act, removing federal oversight from states with a history of racial discrimination at the polls, Justice Ginsburg dissented. When the court recently decided that the Hobby Lobby craft-store chain should not be required to cover contraception for its employees, Justice Ginsburg dissented.

The Columbia Law School graduate is not always playing defense; she’s written some forceful majority opinions as well. In 1996, for instance, the court ruled that the Virginia Military Institute’s (VMI) male-only admission policy was unconstitutional, and Justice Ginsburg took the opportunity to issue a wide-ranging warning about the dangers of gender stereotyping. “The notion that admission of women would downgrade VMI’s stature,” she wrote, “is a judgment hardly proved, a prediction hardly different from other ‘self-fulfilling prophecies’ once routinely used to deny rights or opportunities.” Legal scholars note that whether she’s voicing the court’s decision or contesting it, her decisions have a rare sense of empathy. “Justice Ginsburg knows the court’s cases are ultimately about people, their lives, and their livelihoods,” writes Richard J. Lazarus, a Harvard University law professor.

Even when she’s writing about issues of great importance to her, like the rights of women and minorities (Ginsburg was a lawyer for the ACLU before she became a judge), she manages to be both withering and polite, her tone that of an increasingly impatient teacher. In person, she is delicately mannered and serene; during our interview, she remained as still as the chair she sat in, never fidgeting or checking the time.

The decor in her chambers is a mix of scholastic austerity and grandmotherly comfort: A stack of Harvard Law Reviews sat next to an elaborate, custom-made bobblehead doll of the justice herself; photos of her with President Obama and with Condoleezza Rice, among other prominent politicians, hung alongside snapshots of her family: her husband, Martin, who died in 2010, and her son, daughter, and four grandchildren. She has a taste for modernist art (Josef Albers is among her favorite painters) and a feel-good taste in coffee-table books: a collection of New Yorker cartoons, a book of photos called Mothers & Daughters.

Ginsburg seemed confident that the court would rebound from its recently restrictive stance on women’s rights, although she didn’t have a precise answer for why she felt that way. She describes her dissents as outlets not for her anger but for her optimism: “When you write a dissent, you’re writing for a future court that will see the error into which your colleagues have fallen.”

ELLE: The court’s decision in Hobby Lobby—that a privately held company can exclude contraception coverage from employee health plans based on its owners’ religious objections—was the most controversial of the last session. Can you talk about your dissent?

RBG: I think there was one line in the dissent that says, “Your right to freedom of speech, your free exercise of religion stops at the other fellow’s nose.” You can swing your arms, but that’s the point you stop. The idea that an employer can force its religious beliefs on a workforce that’s diverse, and contraceptives are an essential part of women’s health care—I thought it was an easy case; I was quite disappointed. Interestingly, the court didn’t rule under the Constitution. They ruled under this Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and if we had a more functional Congress, I think there would have been a big chance that Congress would have amended the [Affordable Care Act] to say a for-profit employer has to provide the same coverage as any employer.

ELLE: You’ve said that the symbol of the U.S. shouldn’t be an eagle but a pendulum. It seems to me that the pendulum has swung in a very conservative direction for women’s rights, but not for gay rights. Why?

RBG: To be frank, it’s one person who made the difference: Justice [Anthony] Kennedy. He was a member of the triumvirate used to [reaffirm] Roe v. Wade in the Casey case, but since then, his decisions have been on upholding restrictions on access to abortion.

ELLE: The first time you argued before the Supreme Court as a lawyer was in 1973, on behalf of Sharon Frontiero, an Air Force lieutenant who sued because under military rules she had to prove that her husband was “dependent” on her to get housing and medical benefits for him. [Servicemen, meanwhile, were automatically granted benefits for their wives.] What was it like to stand before the justices?

RBG: I had, I think, 12 minutes, or something like that, of argument. I was very nervous. It was an afternoon argument. I didn’t dare eat lunch. There were many butterflies in my stomach. I had a very well-prepared opening sentence I had memorized. Looking at them, I thought, I’m talking to the most important court in the land, and they have to listen to me and that’s my captive audience.

ELLE: And then you relaxed?

RBG: I felt a sense of empowerment because I knew so much more about the case, the issue, than they did. So I relied on myself as kind of a teacher to get them to think about gender. Because most men of that age, they could understand race discrimination, but sex discrimination? They thought of themselves as good fathers and as good husbands, and if women are treated differently, the different treatment is benignly in women’s favor. To get them to understand that this supposed pedestal was all too often a cage for women—that was my mission in all the cases in the ’70s. To get them to understand that these so-called protections for women were limiting their opportunities. I try to have them think what they would like the world to be like for their daughters and granddaughters. I think it makes a big difference if someone has a close relationship with a girl growing up. I saw it in my old chief [the late William H. Rehnquist]. He, in the ’70s, every case except one, he was on the other side, but he wrote the most wonderful decision upholding the Family Medical Leave Act. I attribute that to his close association with his granddaughters. His daughter had divorced. He became a substitute father for those children, and I think it made a difference.

ELLE: Do you think the pendulum might swing back in a more progressive direction on women’s rights in your lifetime?

I think it will, when we have a more functioning Congress. It’s what happened after Lilly Ledbetter’s case. The [majority’s] failure to understand that a woman who is one of the first in a field that has been occupied by men—she doesn’t want to rock the boat, she doesn’t want to be seen as a troublemaker, and besides, they didn’t give out the pay figures. So, if she had sued early on, they would have said, “She’s paid less because she doesn’t do the job as well.” Ten, 15 years later, and she’s had good performance ratings—they can’t say that anymore. Once that defense was removed, then they say, “Oh, sorry, you’ve sued too late.” When she has a winnable case, she has sued too late. My people didn’t understand that, but Congress did, and they acted swiftly to change it. With this Congress, there’s no chance.

ELLE: What have been the finest and worst moments for the rights of women during your tenure on the court?

RBG: A very good case was the VMI case. People said, “You’re trying to end single-sex schools!” I said, “Look at the brief filed by the Seven Sisters!” The idea was that a state cannot make an opportunity available to one sex and have nothing of the same quality for the other sex. That was a high moment, especially when the old chief joined the judgment. So Scalia was left the only dissenter. I will admit that the reason Justice Thomas wasn’t sitting at that case is he had a son enrolled in VMI. That was a very high point. Of course, Hobby Lobby is disappointing.

ELLE: What do you make of the term activist judge?

RBG: Depends on whose ox is being gored. You think of activism, Congress is supposed to make the laws. So, it passed a campaign finance law. This court says, “No, Congress, you can’t do that.” This court is labeled conservative, but it has held invalid more statutes than most courts. That’s why I say that activism is like “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Even more activist than striking down the campaign finance laws was the Voting Rights Act case. That was originally passed in 1965. It was renewed successively, most recently by overwhelming majorities on both sides of the aisle in Congress. If anybody can have a grasp on voting rights and their importance, it’s the members of Congress. Yet this court held the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional. So the answer to the question: If a judge is called an activist, you know the person saying that doesn’t like the decisions.

ELLE: On what ruling would you say you found yourself in a surprising alliance with your conservative colleagues?

RBG: I side with them all the time in cases that are not great constitutional cases. Most of the cases we hear involve statutory interpretations. So, the divisions that the press plays up, the five-four division, they’re not in your everyday procedure, a provision of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, or a tax case.

ELLE: Has there been a conservative decision that’s really infuriated you?

RBG: The ones that I mentioned…the Voting Rights Act case—Justice Scalia’s opinion—and Hobby Lobby. That’s the good thing about dissenting opinions: You can spell out your reasons. I hope that if it’s a statutory case like Hobby Lobby that Congress will change [the law]. If it’s a constitutional decision, Congress can’t do anything about it, but a later court can. This court has a history of recognizing decisions that were not right and overruling them.

ELLE: It’s part of Washington lore that you and Justice Scalia are good friends and opera buddies. I have to ask, when he says that the Constitution doesn’t necessarily prohibit discrimination against women, isn’t it hard not to take it personally?

RBG: Justice Scalia and I served together on the DC Circuit. So his votes are not surprising to me. What I like about him is he’s very funny and he’s very smart. If you’d like to see the great double debut of Scalia and Ginsburg at the opera….[Ginsburg picks up a framed photo from behind her desk.] This is when we were supers [opera extras] for Ariadne auf Naxos.

ELLE: Oh, my, that’s a great photo. When is this from?

RBG: It’s from 1994, and we were supers together again, some time after 2010, in the next production of Ariadne, but I have no photographs from that…. The other thing is that we both share a lot about family…. Mostly I like him, as I said, because he makes me laugh, and I don’t mind that he writes very attention-grabbing dissents. I think his dissent in the VMI case is classic for him. [She points to another photograph.] That one shows the two of us in 1994 when we were on a delegation to India. So there we are on a very elegant elephant. My feminist friends say, “Why are you riding on the back of the elephant?” and I said, “Because of the distribution of weight, we needed to have Scalia in the front.”

ELLE: Can you give me an example of something Justice Scalia has said or done that made you laugh?

RBG: [Pauses. Laughs.] I can’t tell you, because I wouldn’t want to see it in print.

ELLE: Nothing you’d be willing to see?

RBG: He wrote a dissent in the independent counsel case, many years ago before I was on the court, where it starts out something like, “Wolves sometimes come in sheep’s clothing, but this wolf comes dressed like a wolf.”

ELLE: I also saw the photo in your office of you and former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, and Justice Elena Kagan. You’ve served with all of them. Does it make a difference having three women justices?

RBG: Yes, an enormous difference.

ELLE: It’s a great photo.

RBG: Except for Kagan, who has lost about 20 pounds since this was taken.

ELLE: Can you give me an example of a time when having the three of you on the court has made a big difference?

RBG: Well, one clear difference is in all the years that Sandra and I overlapped, invariably one lawyer or another would call me Justice O’Connor. Sandra would say, “I’m Justice O’Connor. She’s Justice Ginsburg.”

ELLE: That’s the biggest difference—that now people can distinguish between you and the other two women on the court?

RBG: [Laughs] Yeah. The other thing is when Sandra left, I was all alone…. I’m rather small, so when I go with all these men in this tiny room—I’m sort of toward the middle, because I’ve been here that long. Now Kagan is on my left, and Sotomayor is on my right. So we look like we’re really part of the court and we’re here to stay. Also, both of them are very active in oral arguments. They’re not shrinking violets. It’s very good for the schoolchildren who parade in and out of the court to see.

ELLE: When you hear about young womennot calling themselves feminist, what doyou think?

RBG: I think they just don’t understand what the word means. The word means that women, like men, should have the opportunity to aspire and achieve without artificial barriers holding them back. It’s not that you don’t like men but that you are for equal citizenship stature of both.

ELLE: I know you can’t comment on upcoming cases, but I’ve been reading about Young v. United Parcel Service, and I was wondering why you think pregnancy discrimination is still an issue?

RBG: I don’t know why, but the Pregnancy Discrimination Act passed in 1978. It was just like the reaction to Lilly Ledbetter: This court said that discrimination on the basis of pregnancy is not discrimination on the basis of sex. How could you reach that conclusion? “Well, it only happens to a woman, so that’s why it can’t be discrimination on the basis of sex.” So Congress passed a law that simply said, “Discrimination on the basis of pregnancy is discrimination on the basis of sex.” So the case you mentioned, this was a woman whose doctor told her she couldn’t lift more than, I think, 20 pounds. For people who were temporarily disabled, the employer would make an accommodation, but the employer said, “We’re not making an accommodation for her because she’s not disabled.” [Due to UPS’s denial, the employee, Peggy Young, had to take unpaid leave and lost her medical coverage for childbirth expenses.]

ELLE: Fifty years from now, which decisions in your tenure do you think will be the most significant?

RBG: Well, I think 50 years from now, people will not be able to understand Hobby Lobby. Oh, and I think on the issue of choice, one of the reasons, to be frank, that there’s not so much pro-choice activity is that young women, including my daughter and my granddaughter, have grown up in a world where they know if they need an abortion, they can get it. Not that either one of them has had one, but it’s comforting to know if they need it, they can get it. Not that either one of them has had one, but it’s comforting to know if they need it, they can get it. The impact of all these restrictions is on poor women, because women who have means, if their state doesn’t provide access, another state does. It’s kind of like it was with divorces in the old days. It used to be that most states had adultery as the only grounds for divorce. So people were off to Nevada and got divorced there. Then, finally, other states woke up, and now divorce for incompatibility—there’s not a single state that doesn’t have that. I think that the country will wake up and see that it can never go back to [abortions just] for women who can afford to travel to a neighboring state…that all of these restrictions are operative only as to poor women. When people wake up to that, then I think there won’t be any question about access for all women.

ELLE: When people realize that poor women are being disproportionately affected, that’s when everyone will wake up? That seems very optimistic to me.

RBG: Yes, I think so. They’re not conscious of it now. I mean, you have to think pretty deeply. A girl will think, Well, I’m okay, I don’t have any problem. But it makes no sense as a national policy to promote birth only among poor people…. And I think that campaign finance will be overturned. There has to come a point where people realize: How can we pretend to be a democracy when you can buy a candidate?

ELLE: When it comes to abortion rights, does the pendulum have to swing in a more conservative direction before it starts to swing back?

RBG: No, I think it’s gotten about as conservative as it will get.

ELLE: I’ve heard you say that if you were being nominated today, your work at the ACLU would disqualify you from being on the bench. Does that make you worry at all about this bench’s legacy on the issues most important to you?

RBG: I mentioned before that dissents are very important. Let’s go back to the time of World War I and the restrictions on speech. Brandeis and Holmes wrote a number of dissents just for themselves. They are all today unquestionably the law of the land, those dissents. Going back even to the most dreadful decision the court ever handed down, Dred Scott [in which the court ruled that slaves “had not rights which the white man was bound to respect”], there were two dissents. The one by Justice Curtis is particularly good. So I’m optimistic that in the long run that my dissenting opinions will be recognized as the position of this court.

ELLE: I’m not sure how to ask this, but a lot of people who admire and respect you wonder if you’ll resign while President Obama is in office.

RBG: Who do you think President Obama could appoint at this very day, given the boundaries that we have? If I resign any time this year, he could not successfully appoint anyone I would like to see in the court. [The Senate Democrats] took off the filibuster for lower federal court appointments, but it remains for this court. So anybody who thinks that if I step down, Obama could appoint someone like me, they’re misguided. As long as I can do the job full steam…. I think I’ll recognize when the time comes that I can’t any longer. But now I can. I wasn’t slowed down at all last year in my production of opinions.

ELLE: If you were going to start a women’s-rights project today like the one you started at the ACLU in the ’70s, what would be the issues on your agenda?

RBG: Well, they wouldn’t be what ours were. We had clear targets. That is, we wanted to get rid of every explicitly gender-based law, and the statute books were riddled with them, federal and state. Now discrimination is more subtle. It’s more unconscious. I think unconscious bias is one of the hardest things to get at. My favorite example is the symphony orchestra. When I was growing up, there were no women in orchestras. Auditioners thought they could tell the difference between a woman playing and a man. Some intelligent person devised a simple solution: Drop a curtain between the auditioners and the people trying out. And, lo and behold, women began to get jobs in symphony orchestras. When I told this story a couple of years ago, there was a violinist who said, “But you left out one thing. Not only do we audition behind a curtain, but we audition shoeless, so they won’t hear a woman’s heels coming onstage.”

Then these other things: How do you have a family and a family life and a work life? So some people are writing about Justice Sotomayor and Justice Kagan and saying to rise to the top of the tree in the legal profession, you have to forgo a family. Where are these people? What about Justice O’Connor? She had three sons. I have two children. Pat Wald was with me on the DC Circuit and had five children. It’s true that you need a spouse who believes you should have a chance to do whatever your talent and hard work enable you to do. But it’s still a problem that a lot of young women are experiencing—particularly with law firms that demand so many hours per week—and solving that problem will not be easy. But it is getting better. More and more there are men, like my son-in-law, who are at least an equal parent.

ELLE: Those are more cultural issues, then, as opposed to legal ones. Is that where you see…

RBG: Yeah, but you can do things that facilitate it, like the Family Medical LeaveAct. Our government is not doing as much as some European governments, but it’s beginning to recognize that all workers should be able to take time off if they have a sick spouse, sick child, sick parent. The law can be a part of social change. It won’t create the change over-night. Even starting when my daughter was born, in 1955, the word day care wasn’t known in this country. When I was going to law school and transferred to Columbia, there was this one nursery school in the area, and you could send the child from 9 to 12 or 2 to 5, and that was it. By the time my daughter, who teaches at Columbia, had small children, there were all-day daycare facilities, any number of them, which she could choose from.

RBG: I wanted to ask you about your husband, Martin Ginsburg. He was a tax-law expert and Georgetown professor. I have a copy of his cookbook, Chef Supreme [which Martha-Ann Alito, among other Supreme Court spouses, put together after his death]. I know you married him a few days after you graduated from Cornell in 1954—he seems unusual among men of his generation. How did that make a difference in your career?

RBG: It made an enormous difference. I met Marty when I was 17 and he was 18. He was the only boy I had ever met who cared that I had a brain. In the ’50s, too many women, even though they were very smart, they tried to make the man feel that he was brainier. It was a sad thing. Marty had a wonderful sense of humor. He thought that I must be pretty good, because why would he decide that he wanted to spend his life with me? He always made me feel like I was better than I thought I was. He was so confident in his own ability that he never regarded me as any kind of threat. On the contrary, he tried to do everything he could to boost my career. He also decided—and I was very lucky about this—that when my daughter was born, he read something that said the first year is very important, that’s when the child’s personality gets formed, so he spent a lot of time with my daughter when she was a baby. And the kitchen was his domain.

When I was appointed to the Court of Appeals in 1980, here in DC, so many people asked, “It must be hard on you to be commuting back and forth.” I said, “What makes you think I’m doing that?” Of course Marty moved to DC….

When I was introduced at functions in town, the introducers would often say, “This is Justice Ginsburg,” and the hand would go out to Marty. Women were still very rare on the federal bench. Marty would tell them, “She’s the judge.”

ELLE: It’s a hackneyed idea, but some people still think it’s hard to be a woman in authority and also be likable. You’re both.

RBG: I am what I am. The authority that I have is this position, and I work very hard on the opinions that I write because that’s how I think I earn respect, when people see the quality of the reasoning. [She grins.] A student at NYU started some- thing with Notorious R.B.G. and then somebody at Stanford did another T-shirt.

ELLE: I’ve been seeing them everywhere! When was the first time you saw the shirt?

RBG: I think it was Janet Benshoof, who in the old days headed up the ACLU’s reproductive-freedom project. Now she has an NGO of her own [the Global Justice Center]. She had some interns, and they did this sort of rap-style thing. It’s a sketch.

ELLE: What do you make of all that?

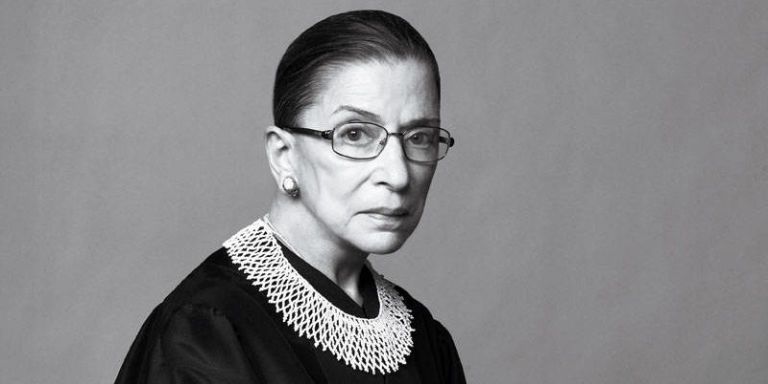

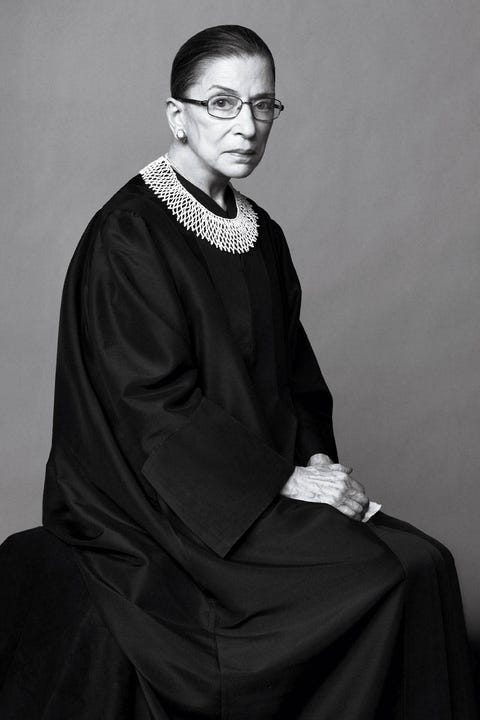

RBG: I mean, it’s amazing that even you had the photographer come in. Here I am, 81 years old, and people want to take my picture.

ELLE: Do you watch TV?

RBG: Last time I watched TV was the presidential debates.

ELLE: Do you ever get the news from television?

RBG: Yes, I have a personal trainer come here twice a week at seven o’clock. And those days I watch the News Hour from 7 to 8.

ELLE: What’s your favorite way to exercise?

RBG: I have a trainer who tells me what to do. I do weight lifting, the elliptical, stretches, push-ups.

ELLE: That’s impressive. When did you start working out like that?

RBG: 1999, I had colorectal cancer. I had months and months of chemotherapy and radiation, and when I got finished with all that I was not in the best shape. My husband said, you got to get yourself a personal trainer, and that’s when it began.

ELLE: What did your parents think of your career?

RBG: My mother died when I was 17. I think she would have been very surprised, but I think she would be very pleased to see the opportunities that I had that she didn’t have. My father thought everything I wanted to do was okay because Marty and I married when I was 21, and my father thought, She can do whatever she wants, because if it doesn’t work out, she has a man to support her.

ELLE: What do you do to relax? I know you’re a big opera buff, but anything else?

RBG: I read novels. I go to opera rehearsals. I love theater. I love the movies. I attended all four operas at Glimmerglass Festival in Cooperstown.

ELLE: Have you read anything good recently?

RBG: I’m reading a book I’m loving. It’s hard to put it down: Someone, by Alice McDermott. Before that I read a wonderful biography of Branch Rickey, who was the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was the man who decided that the color line should end. He was the one who found Jackie Robinson. And the rest is history. Even though I’m not a baseball fan, it was just wonderful. Very revealing about what the society was like.

ELLE: Do you think it would make a big difference to this country to have a female president?

RBG: I think it’s inevitable that we will. I’d like to see that in my lifetime.

This story originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of ELLE.