If you haven’t already heard of the “trendy” online fast-fashion retailer SHEIN before, then brace yourself because this brand is making waves. In the past week alone it has gone viral online three times for selling things that have done more than raise eyebrows. This is the website where you will find Muslim prayer mats being sold as “decorative and floral tassel trim mats”, necklaces with the word Allah (God) in Arabic being sold as part of a multi-pack with other chains saying things like “baby girl” and “scorpio”. And, wait for it, a pendant Swastika necklace for the princely sum of £2.50.

At a time when the number of anti-Semitic hate incidents recorded in the UK has reached a record high, the problems associated with the sale of a symbol steeped in one of the most painful periods of the 20th century seem self-evident. Almost 6 million Jews were killed during the Holocaust and seeing the Nazi symbol is still a triggering experience. There have been calls for a boycott of SHEIN for promoting Nazi paraphernalia and accusations that it is “directly threatening” to the Jewish community.

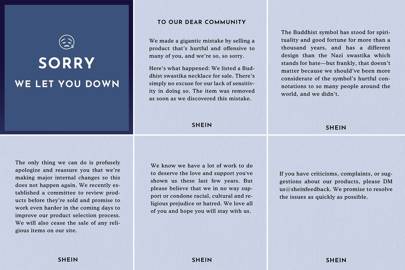

In the wake of increased scrutiny the company pulled the product and issued an apology saying that the Swastika symbol was being sold in the context of its Buddhist and Hindu origins. “We made a gigantic mistake by selling a product that’s hurtful and offensive to many of you, and we’re so, so sorry. Here’s what happened; we listed a Buddhist Swastika necklace for sale. There’s simply no excuse for our lack of sensitivity in doing so. The item was removed as soon as we discovered this mistake.”

The statement goes on to say: “The Buddhist symbol has stood for spirituality and good fortune for more than a thousand years, and has a different design than the Nazi Swastika which stands for hate. But frankly, that doesn’t matter because we should’ve been more considerate of the symbol’s hurtful connotations.”

There is so much that SHEIN’s apology fails to address. Context and details matter. Marketing an item from the east (where the item means one thing) to a consumer in the west (where it means another) carries consequences. The brand completely misses the point about appropriation to ironic levels. The Swastika symbol represents divinity and spirituality in religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. The word Swastika originally comes from Sanskrit and means “conducive to well being’. When drawn with a different indentation to the left or right the meaning changes. The right leaning iteration of this symbol originally meant prosperity and good luck in Hinduism. It was appropriated by the Nazi movement and used for an evil and nefarious cause. Furthermore, even if SHEIN intended to use the left leaning symbol in the Buddhist context, it’s still appropriating what is a sacred symbol in the name of profit. SHEIN appears utterly oblivious to this.

“It’s really upsetting to see something so sacred being sold in this way. They’ve taken my religion and monetised it,” says Tina Mistry, a clinical psychologist based in Birmingham. Tina is of Indian descent and she practices Hinduism. Her mother was a garment worker in Leicester. Having seen what it is like on the factory floor, this is a topic that is close to Tina’s heart. The price point of £2.50 for a religious symbol doesn’t seem right to her. “It feels hugely degrading,” she says. “It’s devaluing religion and sacred symbols. Ordinarily these symbols are made out of real gold and silver. They are precious things that you do not throw away. It’s something you wear to give you protection and to feel closer to God.”

“I don’t think it’s their place to be making money over anything religious,” says Anita Bhagwandas, a Contributing Beauty Director for Glamour UK. Anita grew up in Wales to Indian, Hindu parents and has campaigned about cultural appropriation in the wellness space. She says the sale of these items are misguided. “If anyone was buying the symbol for religious purposes they’d go to a temple,” she says. “You see this kind of appropriation a lot in yoga culture too with the Om sign, for example, being used inappropriately. It’s offensive to Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.”

@sheinofficial / Instagram

SHEIN is part of AliExpress, an online retail service based in China. It’s owned by the Alibaba Group, the world’s largest retailer and e-commerce company, which was co-founded by Jack Ma, China’s second richest man. SHEIN is described online as the world’s largest pure-play fashion company globally. That means it operates only on the internet. For such a big company there’s relatively little information about it online and much of it is conflicting. One of the most detailed descriptions of the company comes from a LinkedIn page and is unverified. It says the brand was set up in 2014 but this doesn’t stack up as SHEIN held a 10th anniversary party in London in 2018. The company is believed to employ between 5,000 and 10,000 people and has addresses registered in Guangzhou and Guangdong in China. There are also claims that SHEIN sold an astonishing volume of goods last year — US$2,700 million to 200 countries.

There are no press or email details on its website or social platforms. The most searched questions about the brand on Google include: “Is SHEIN legit?” and “How does SHEIN sell so cheap?”. With 11.4M followers on its official Instagram account as well as numerous localised pages with many more millions of followers, this is a company with a big social presence. It appears to have grown in popularity via influencers unboxing hauls on YouTube and posting outfits on the gram. Reality TV stars like Georgia Toffolo released a collection with them in February this year and Love Island’s Kendall Rae Knight features in one of their most recent Instagram posts.

Getty Images

So why is a brand that’s so omnipresent still so fuzzy and opaque? It seems to be everywhere and nowhere at once. We’ve reached out to SHEIN for comment and asked for a media interview multiple times over the past 4 days via their UK and global accounts on Instagram and Twitter and on a newly set up feedback page. We have yet to receive a direct response from them. However in a statement seen by Glamour UK the company said it has recently set up a committee to review products before they’re sold. The statement said “we promise to work even harder in the coming days to improve our product selection process. We will also cease the sale of any religious items on our site. We know we have a lot of work to do.”

What happened over the past week with SHEIN taps into the unsavoury side of fashion and it is by no means a one off. “Appropriation is theft of property. It is the act of depriving someone of their cultural and intellectual property. The reason it’s controversial is whether a culture can be owned by someone or not,” says Dr Serkan Delic, a Senior Lecturer in Cultural and Historical Studies at London College of Fashion with research fields in racism and appropriation. Dr Delice managed to steal a quiet moment to chat to me from the floor of a garment factory in Istanbul where he’s conducting research. “Unfortunately appropriation in fashion is extremely prevalent. This is not the first example and it won’t be the last,” he adds.

Getty Images

Dr Delice makes a valid point. This certainly isn’t the first example of religious symbols being adopted by the fashion industry. A similar debate about the use of the crucifix in fashion and popular culture has taken place several times over during the past few decades. In 2018 Pope Francis went as far as to call wearing a crucifix as a fashion item “abuse”. That same year the theme of the Met Gala (fashion’s biggest night out) was Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. It was a large scale, global, overt and glorious example of fashion adopting religious symbolism, references and iconography.

Given that something like the Met Gala is clearly a celebration, where does one draw the line between appreciation and appropriation? Is there a scenario where different cultures can be adopted in a way that’s positive? For Tina Mistry, it starts with attribution and representation. “If you had people consulting from the top these things wouldn’t be happening,” she says, likening appropriation to plagiarising an essay. “It needs to be done in a way where the culture is celebrated and the beauty is shown and people are educated and learn about a culture in a meaningful way.”

Even with more representation, it’s difficult to separate the topic of appropriation from fashion’s obsession with the “cult of new” and its links to capitalism. The pace of production and the pursuit of profit are key reasons why appropriation keeps happening again and again. And it goes way back. “Since the early 19th century fashion has always been defined by originality and profit. It is capitalism’s dearest child,” says Dr Delice. “Designers and retailers turn cultures into commodities to make money. It’s an extremely intense and volatile industry. As long as it continues to be led by this quest for ever increasing profit and spend, appropriation will be unavoidable.”

It’s been a bad week for SHEIN. The most prominent voices calling them out online aren’t buying their apology as genuine. Time will tell if the action SHEIN has committed to results in real improvements. But be under no illusion. The issue of appropriation isn’t specific to fast fashion. The luxury industry and designers have had their fair share of questionable moments over the years in degrees ranging from enthusiastic appreciation to blatant theft.

From Yves Saint Laurent’s meticulous research of Asian culture or Ottoman embroidery; to the multicoloured dreadlock wigs worn by white models on the runway for a Marc Jacobs show; to the carbon copy of a design worn by a Canadian Inuit Shaman by KTZ. The list of examples is extensive. “We need to acknowledge that these things happen not because designers are evil or stupid. They are under pressure to produce at an unsustainable rate.” explains Dr Delice. “We need to reduce the speed so designers are given time for research. Production should be underpinned by knowledge, research and respect for cultures and include the original owners in a way that isn’t tokenistic. But first, we need to slow down.”

The fashion industry has been following a calendar of shows that’s so full and a pace of production that’s so mindless, it is bursting from the seams. But things are changing. A global pandemic, an ecological crisis and a social justice movement is exposing inequality and helping dismantle dominant structures and hierarchies. This is a moment of reckoning where the feedback loop by consumers and on digital media (as demonstrated over the past week for SHEIN) can no longer be ignored.